Slave Cabin Site

Archaeological Dig

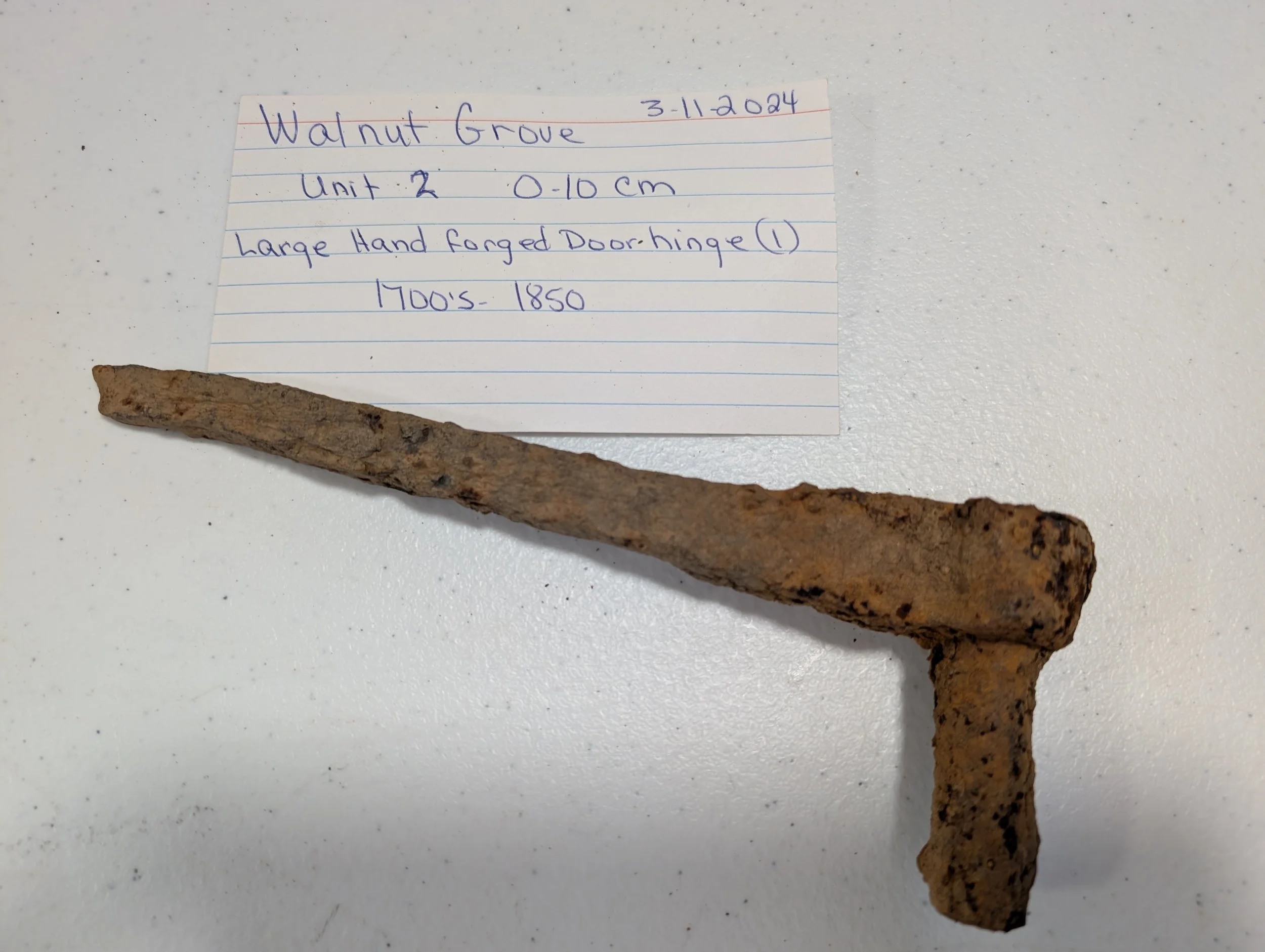

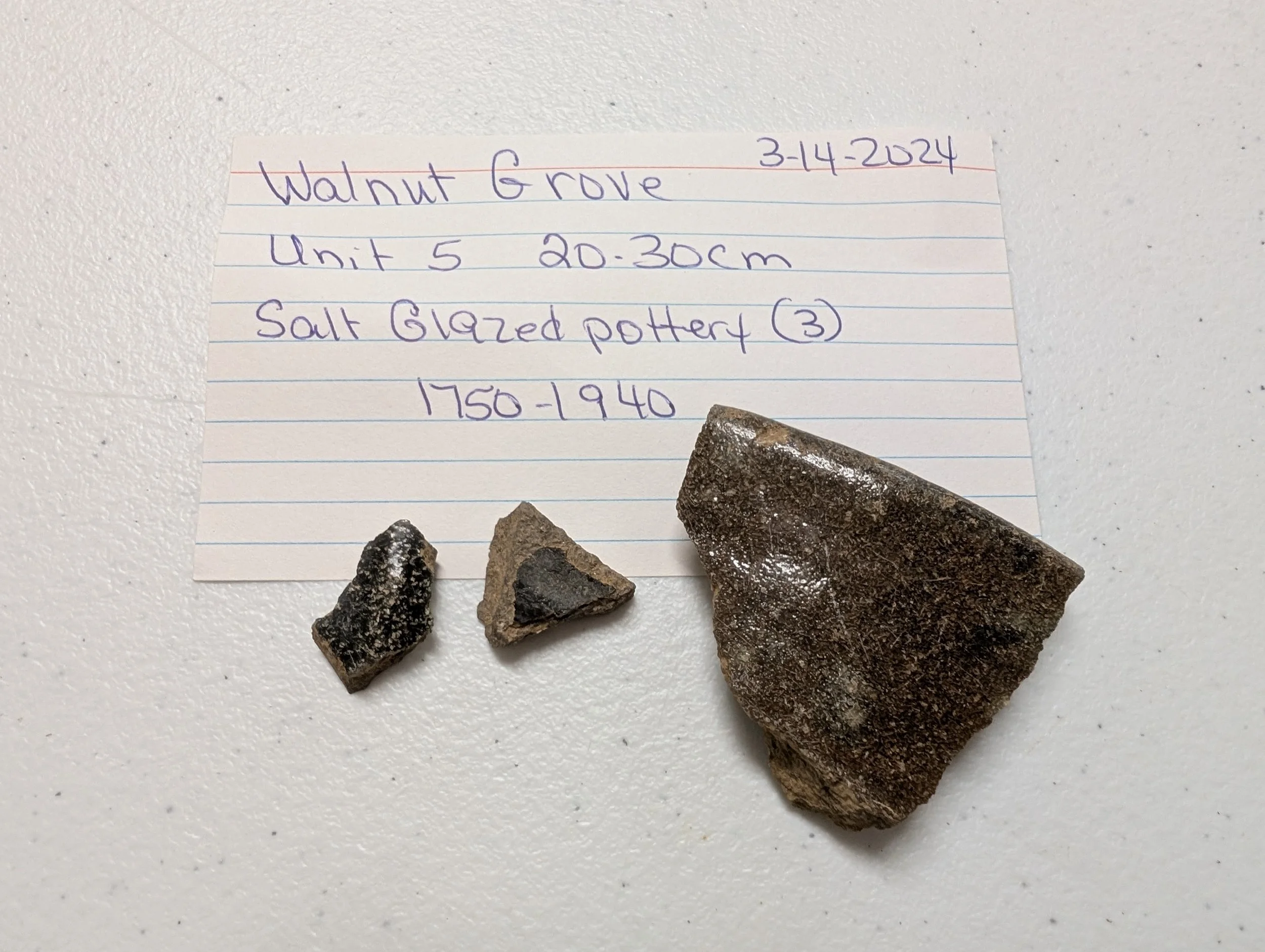

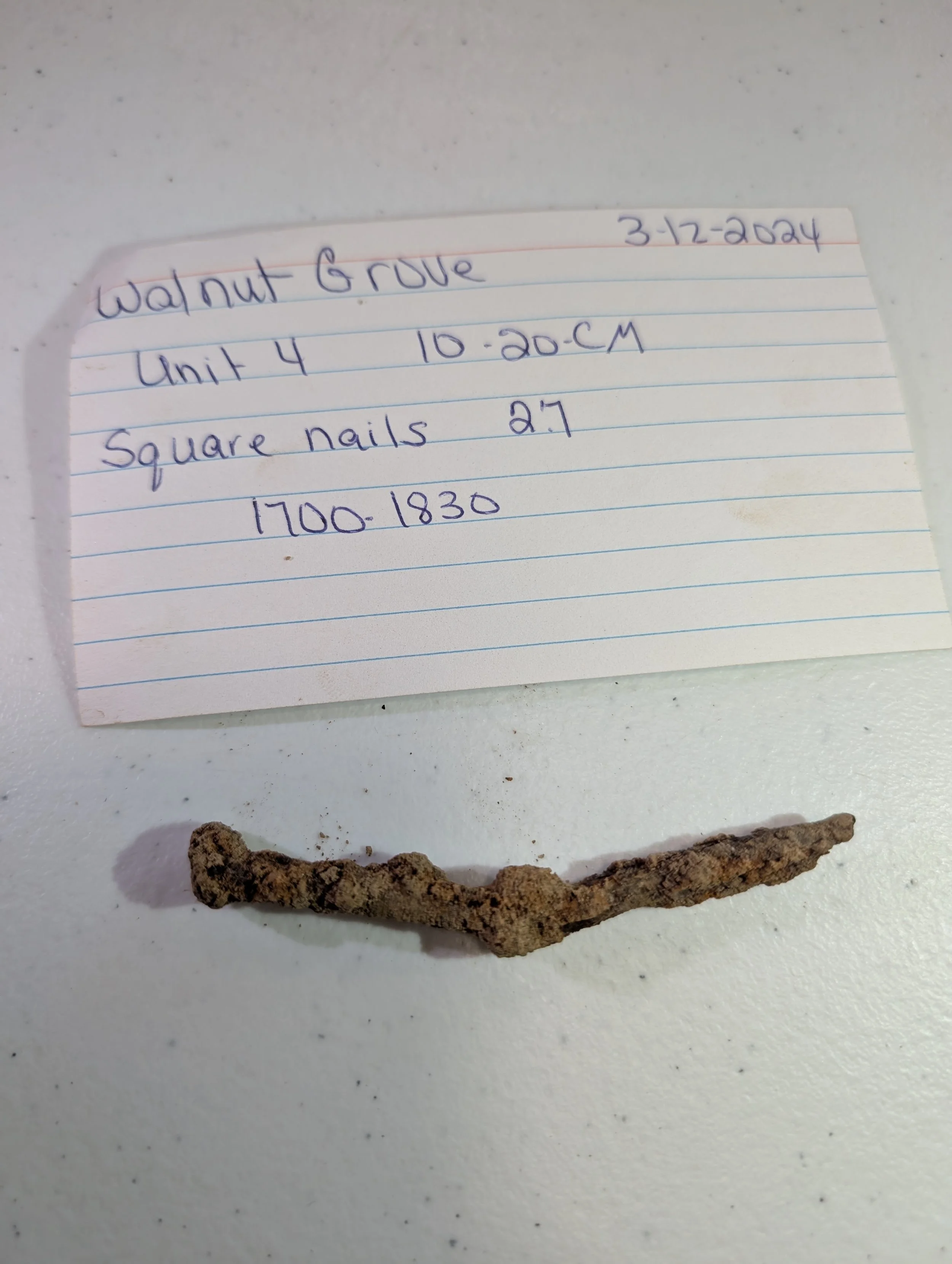

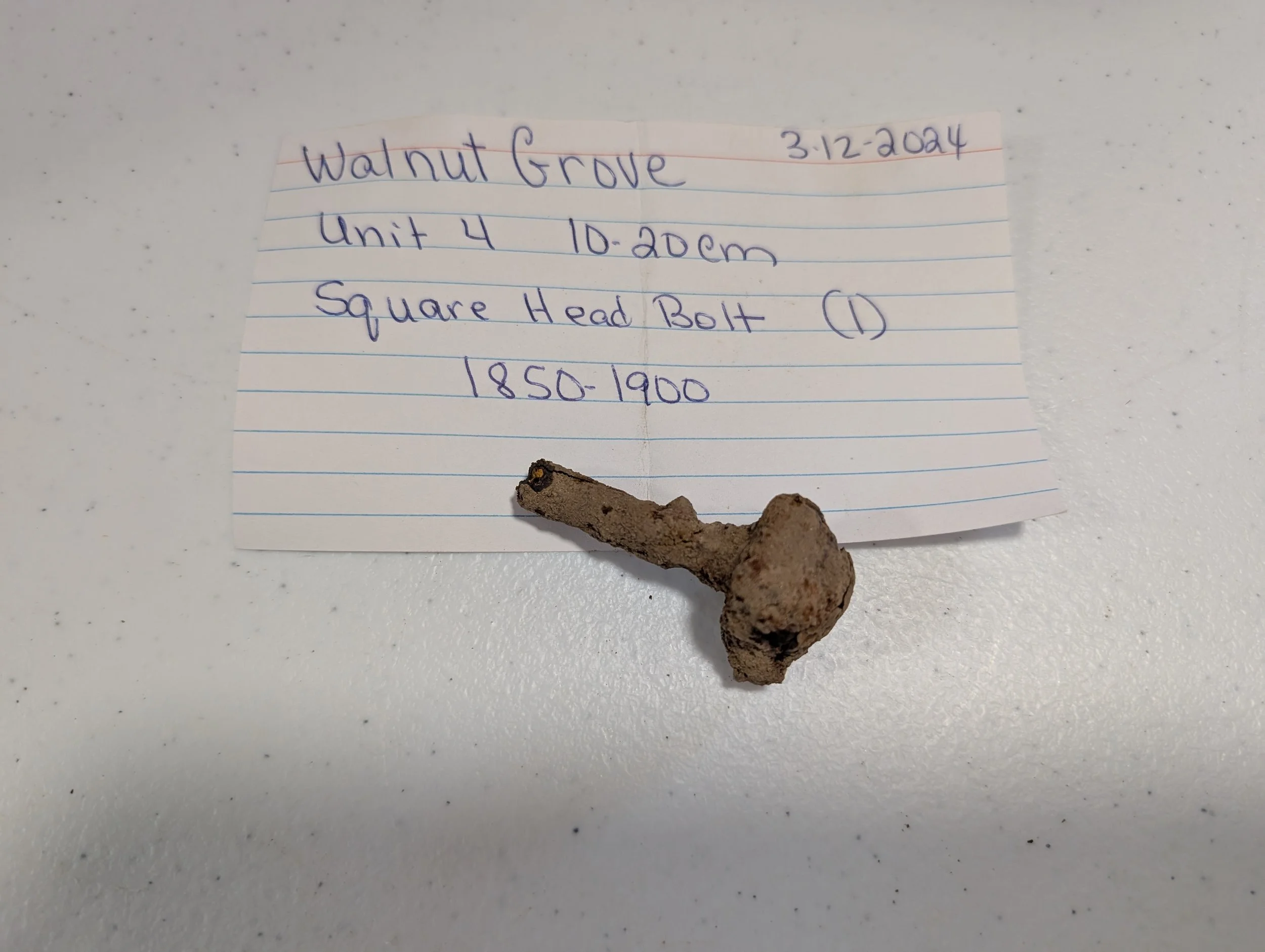

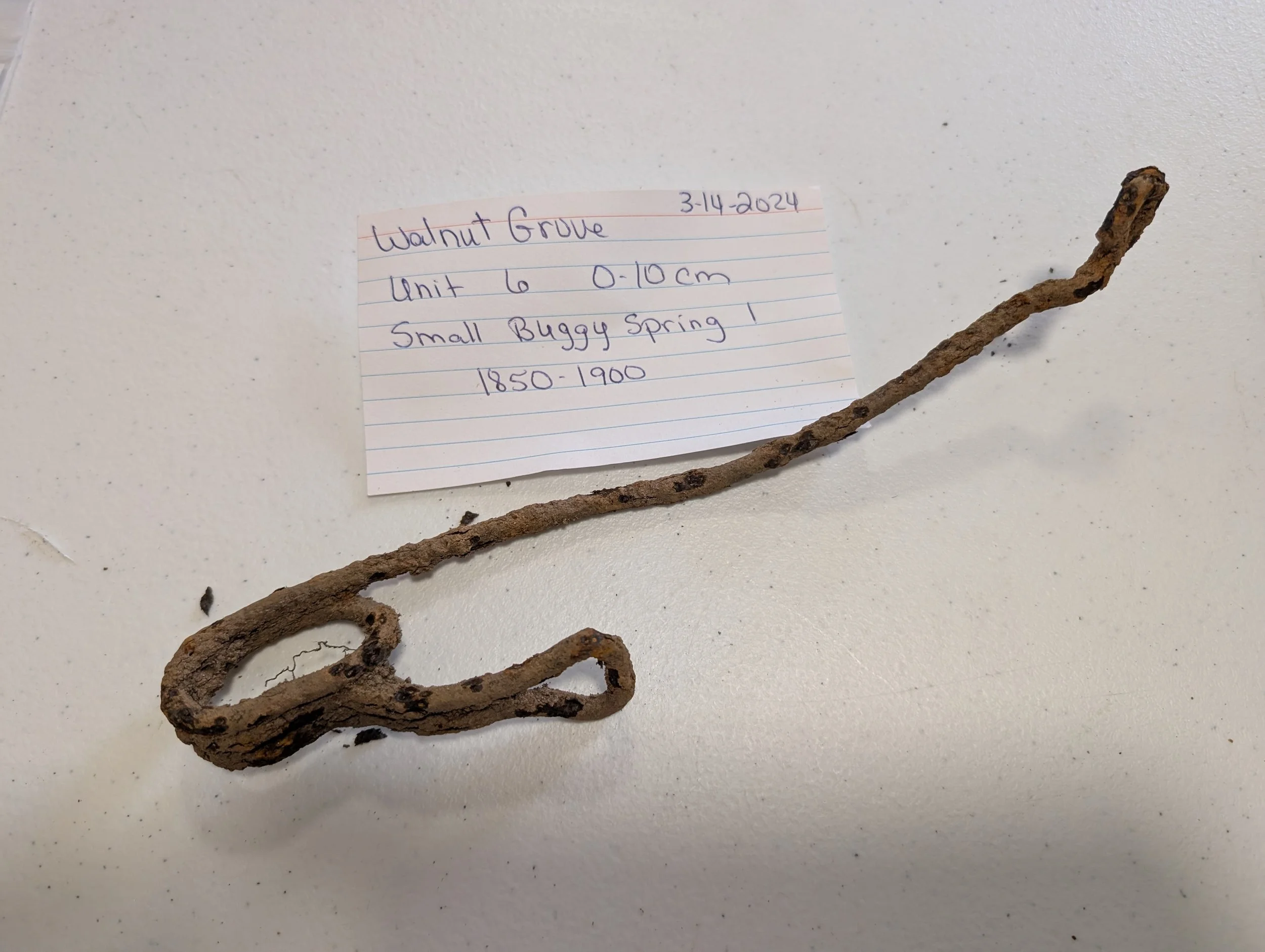

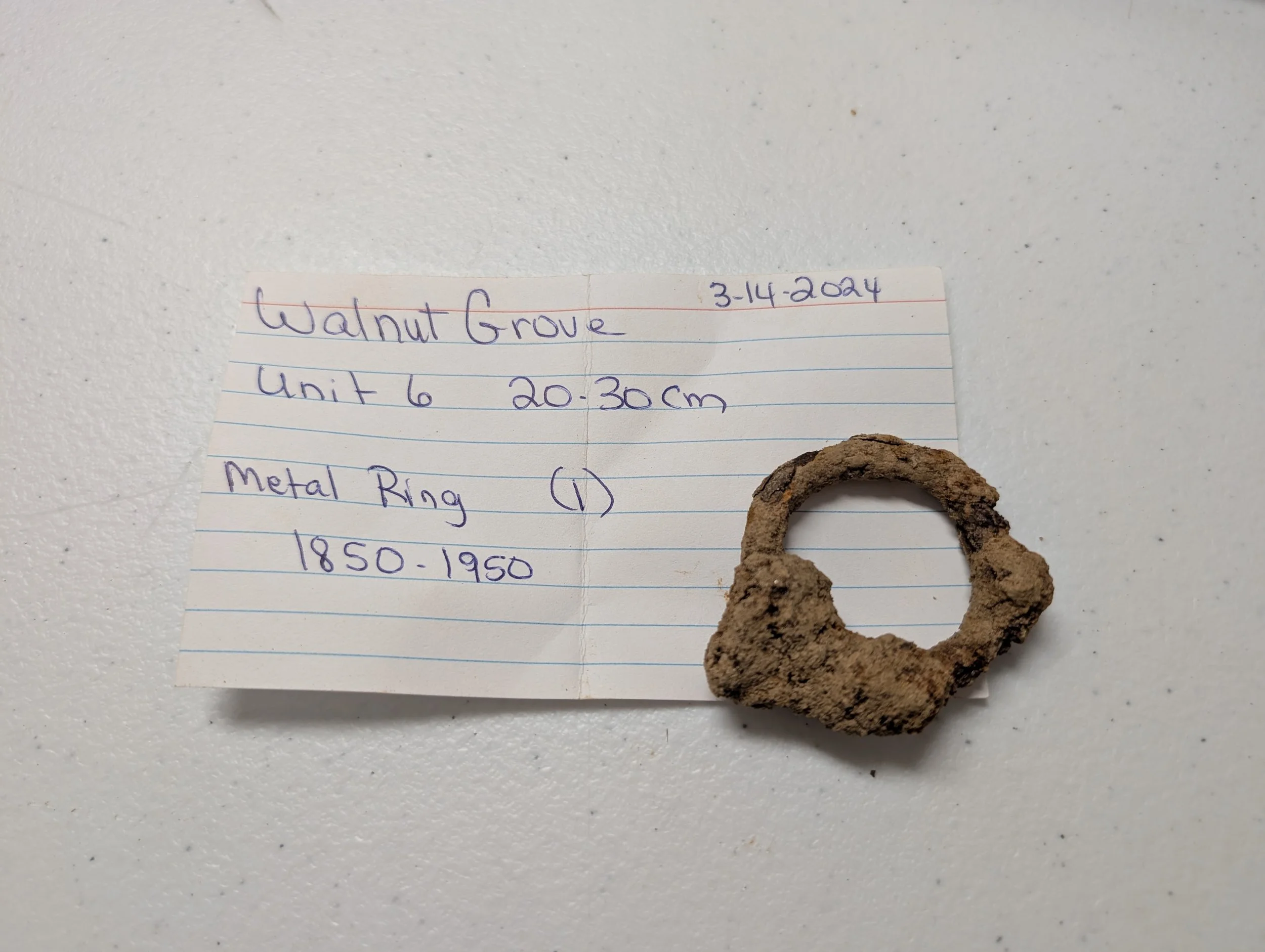

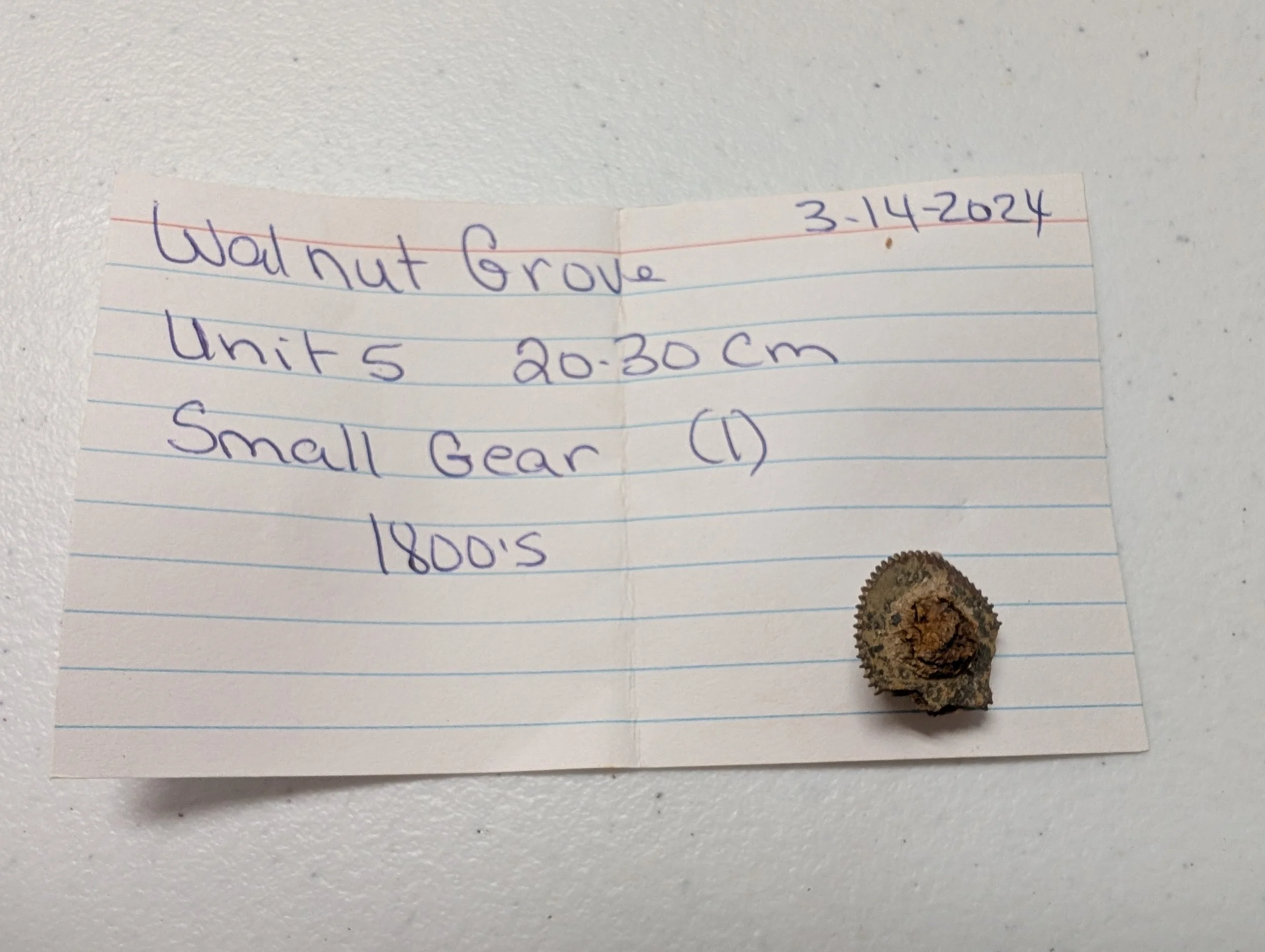

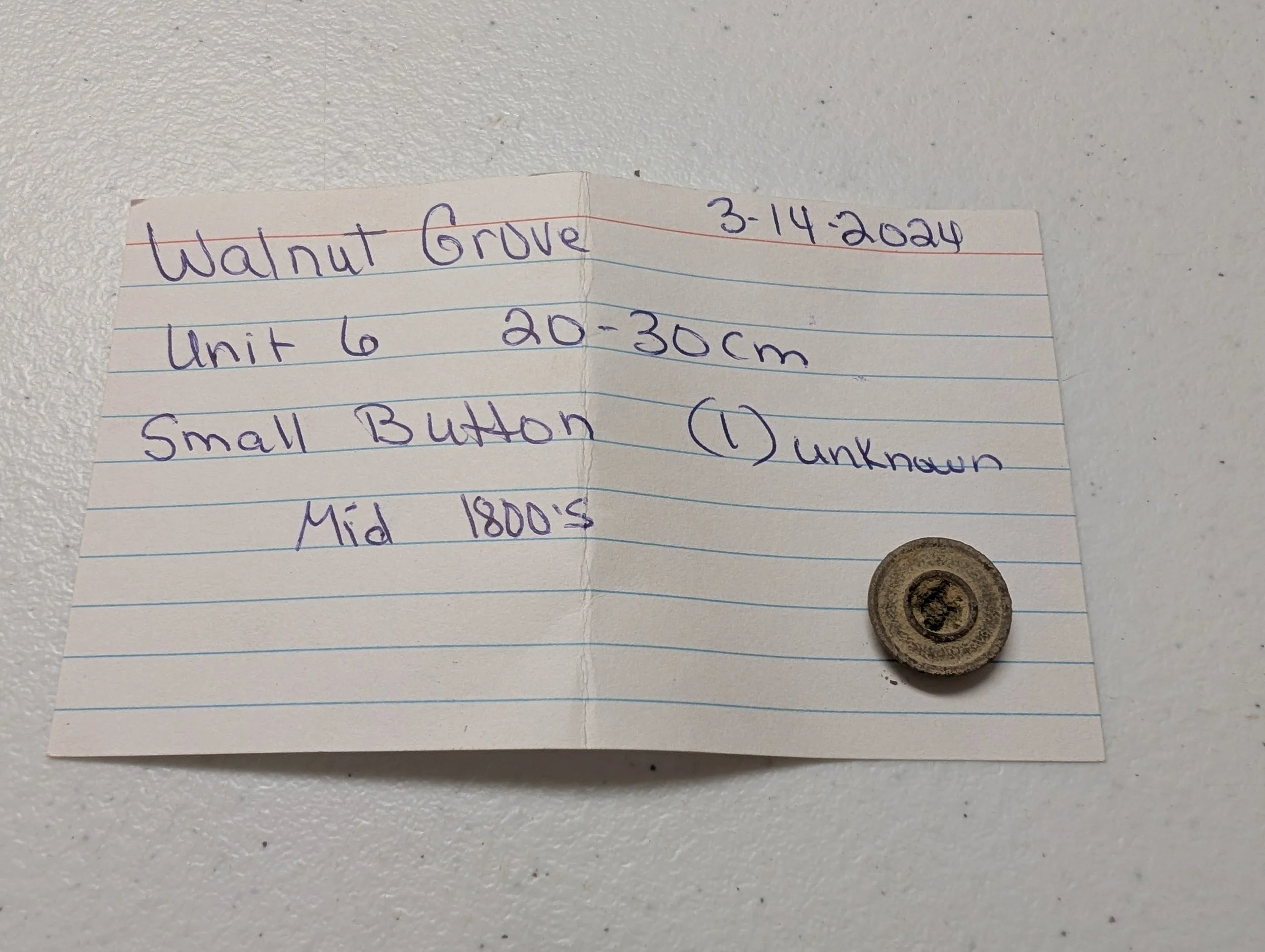

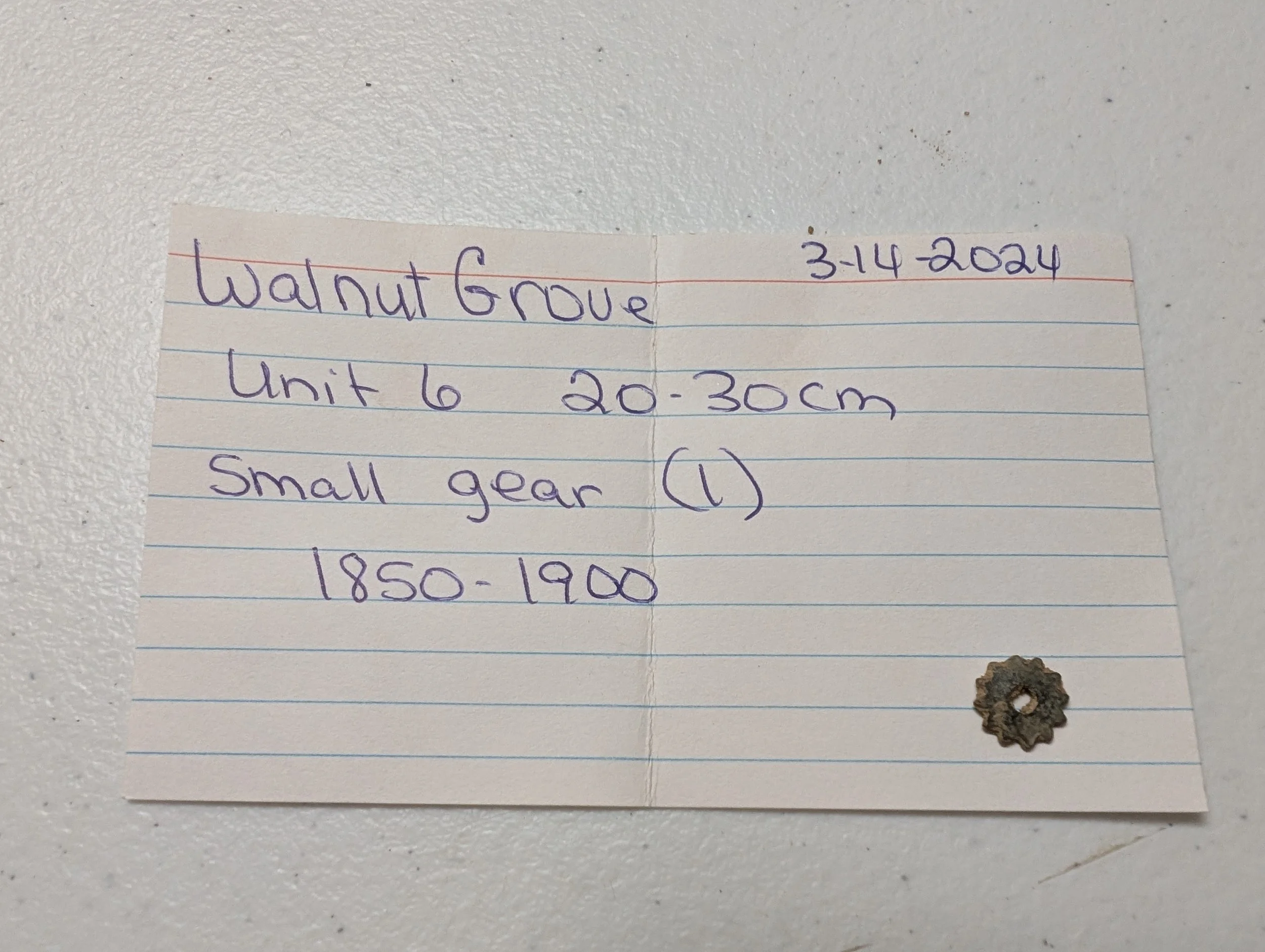

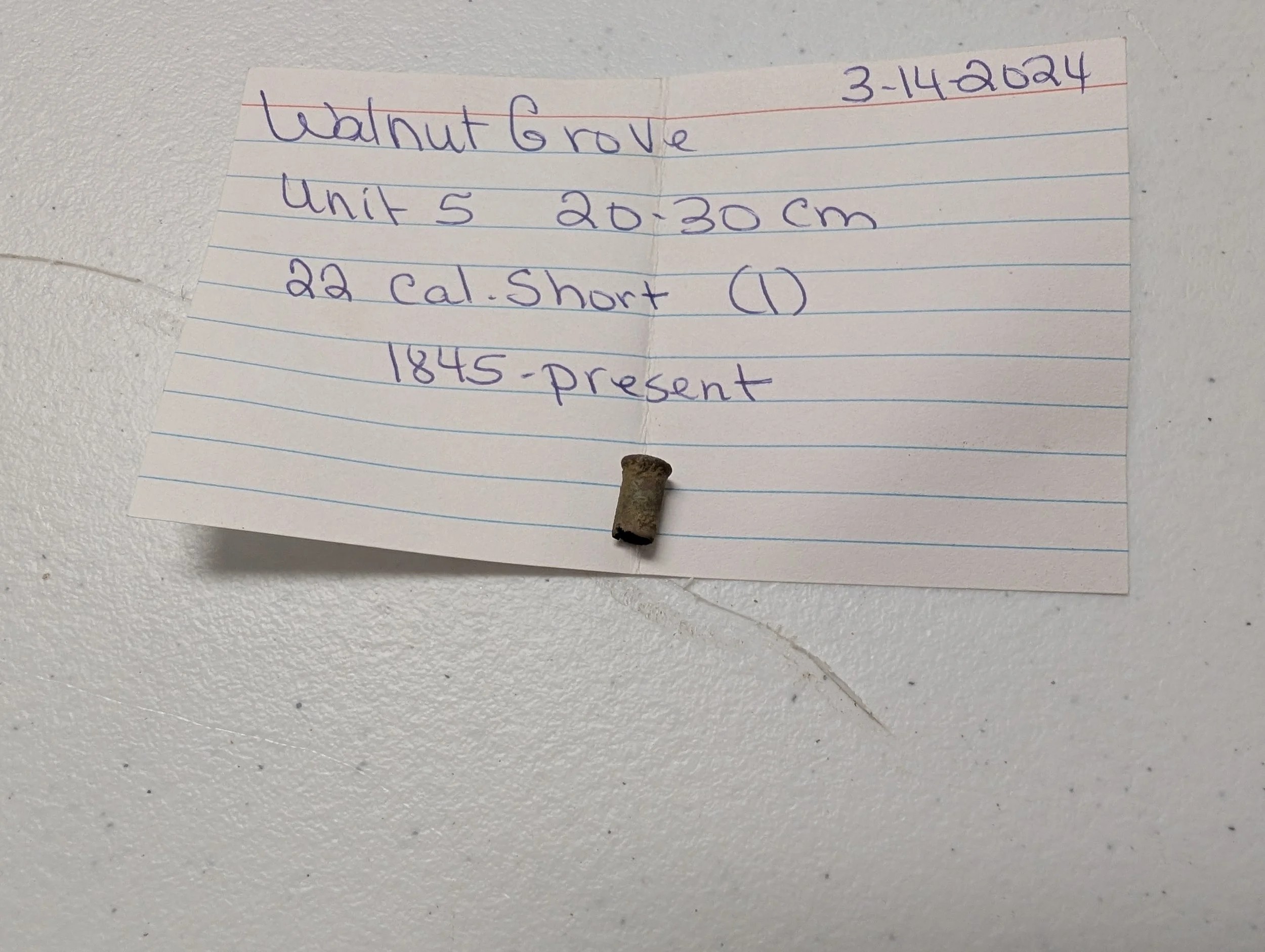

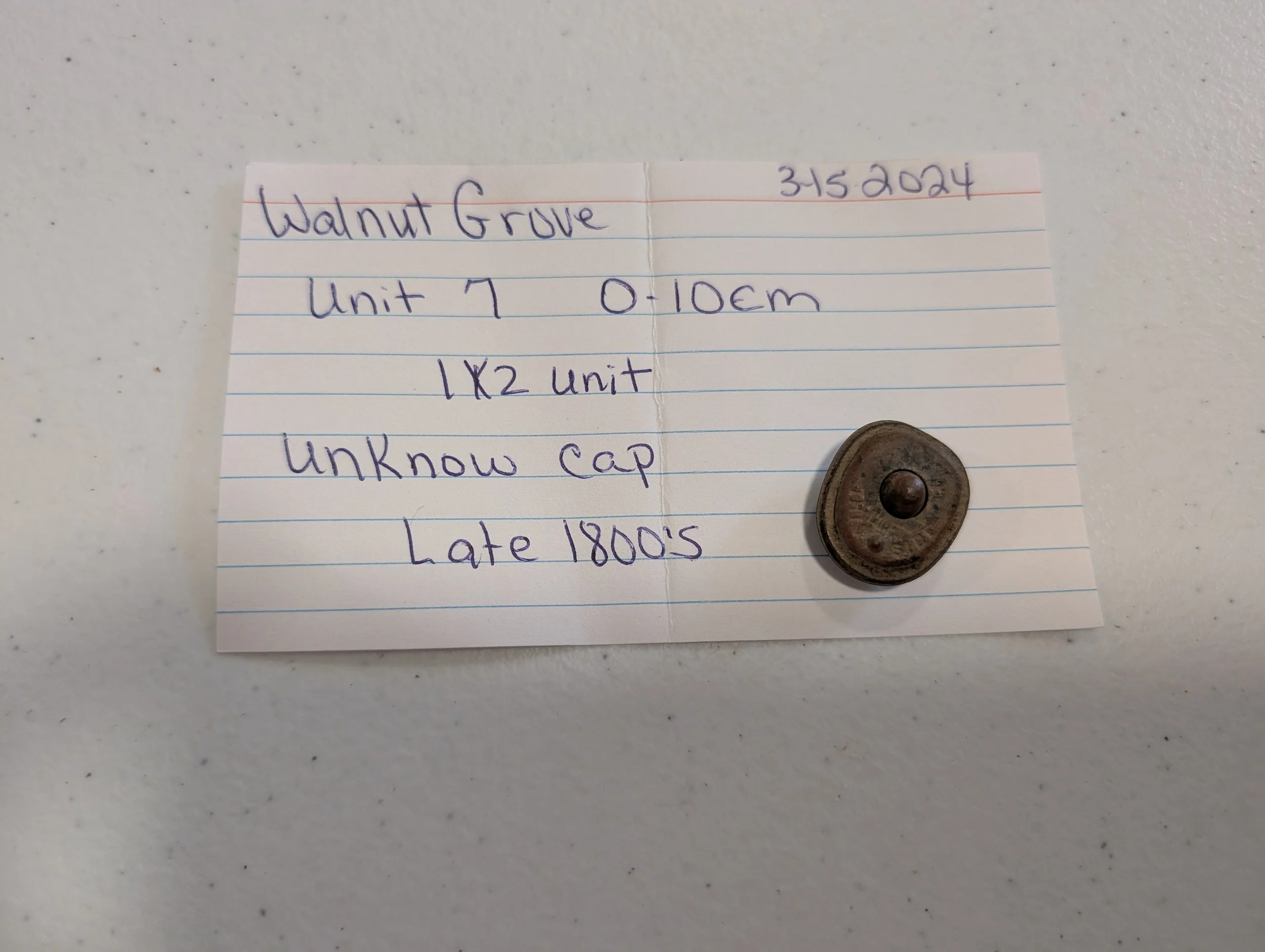

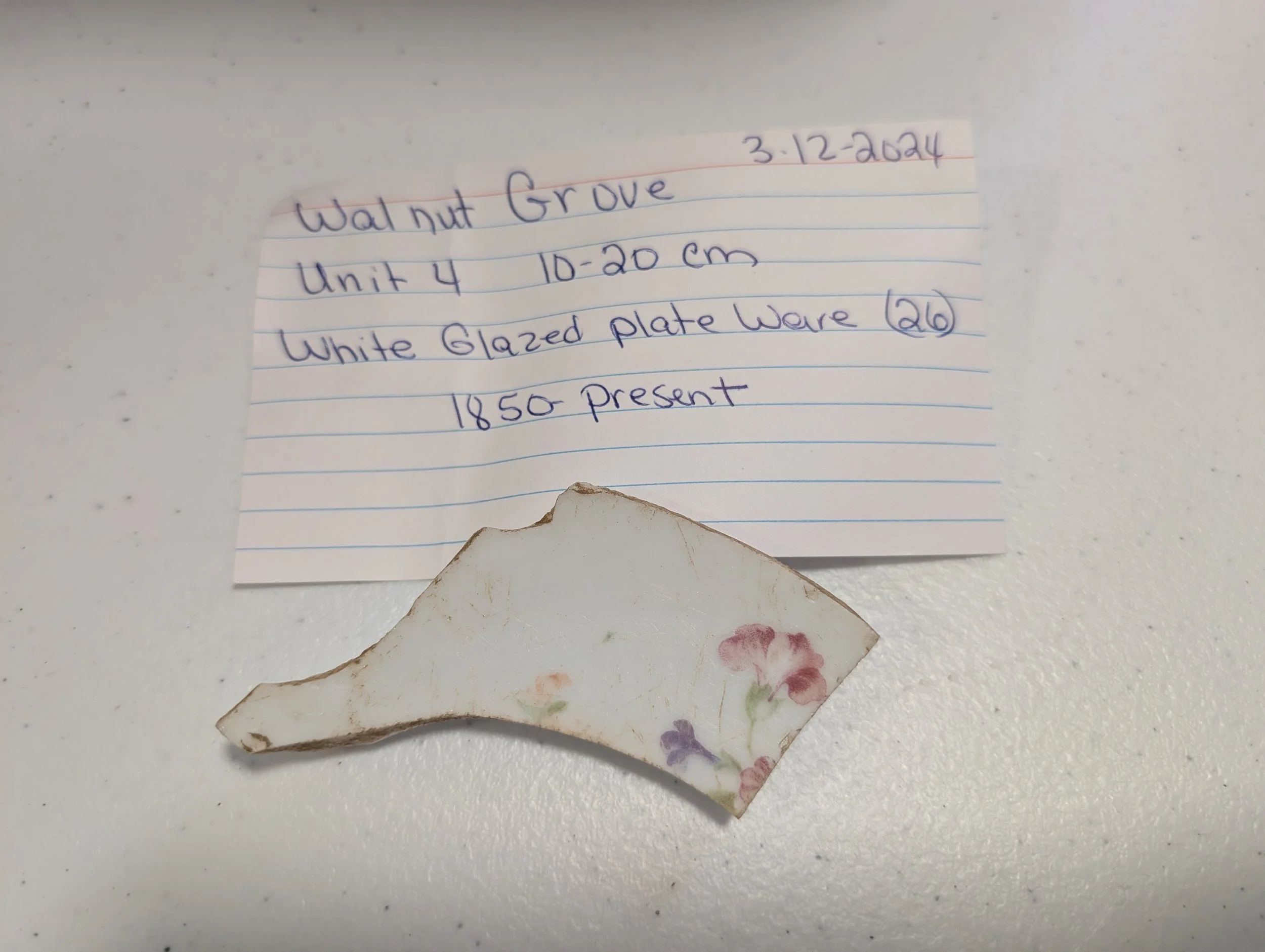

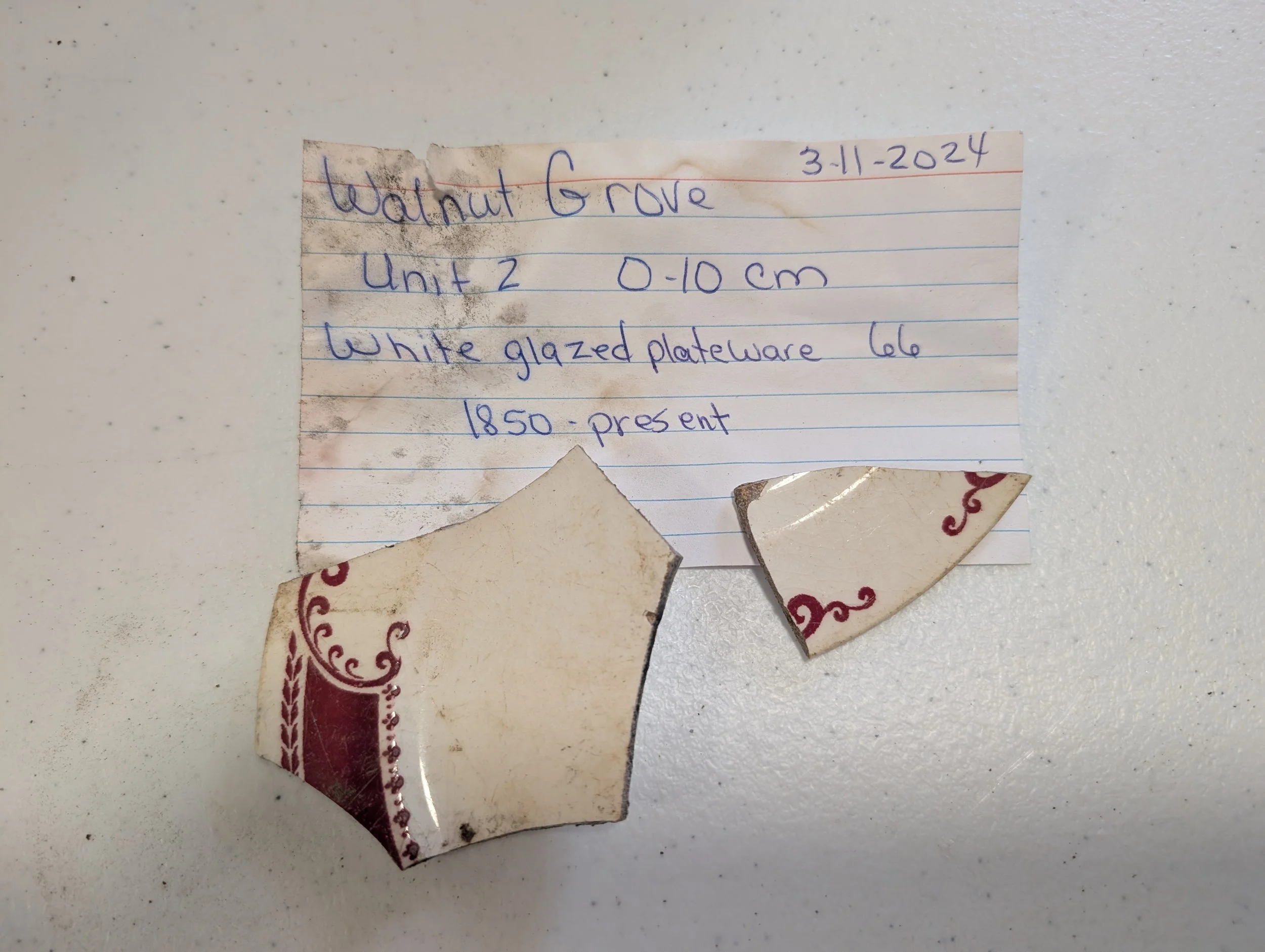

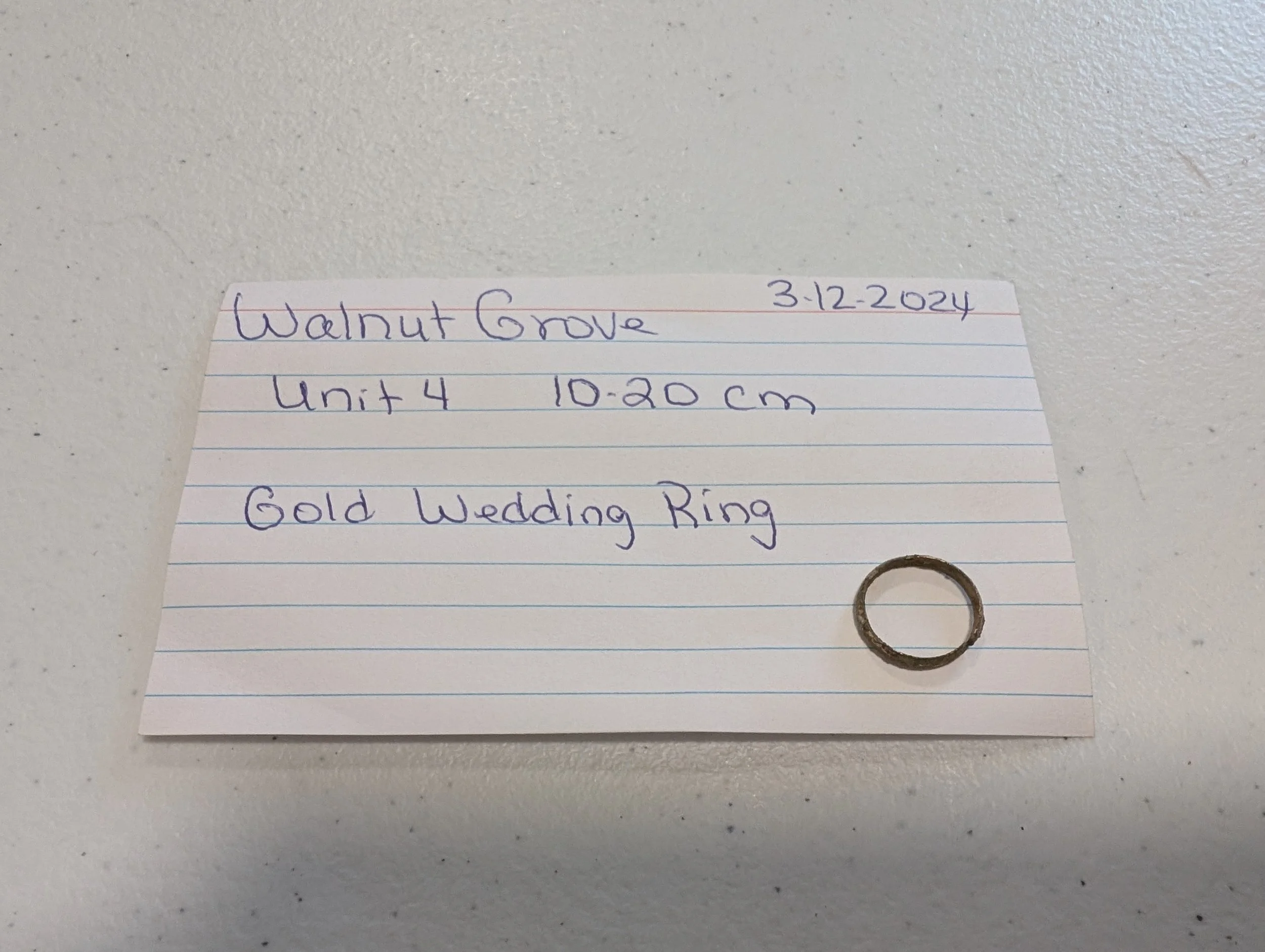

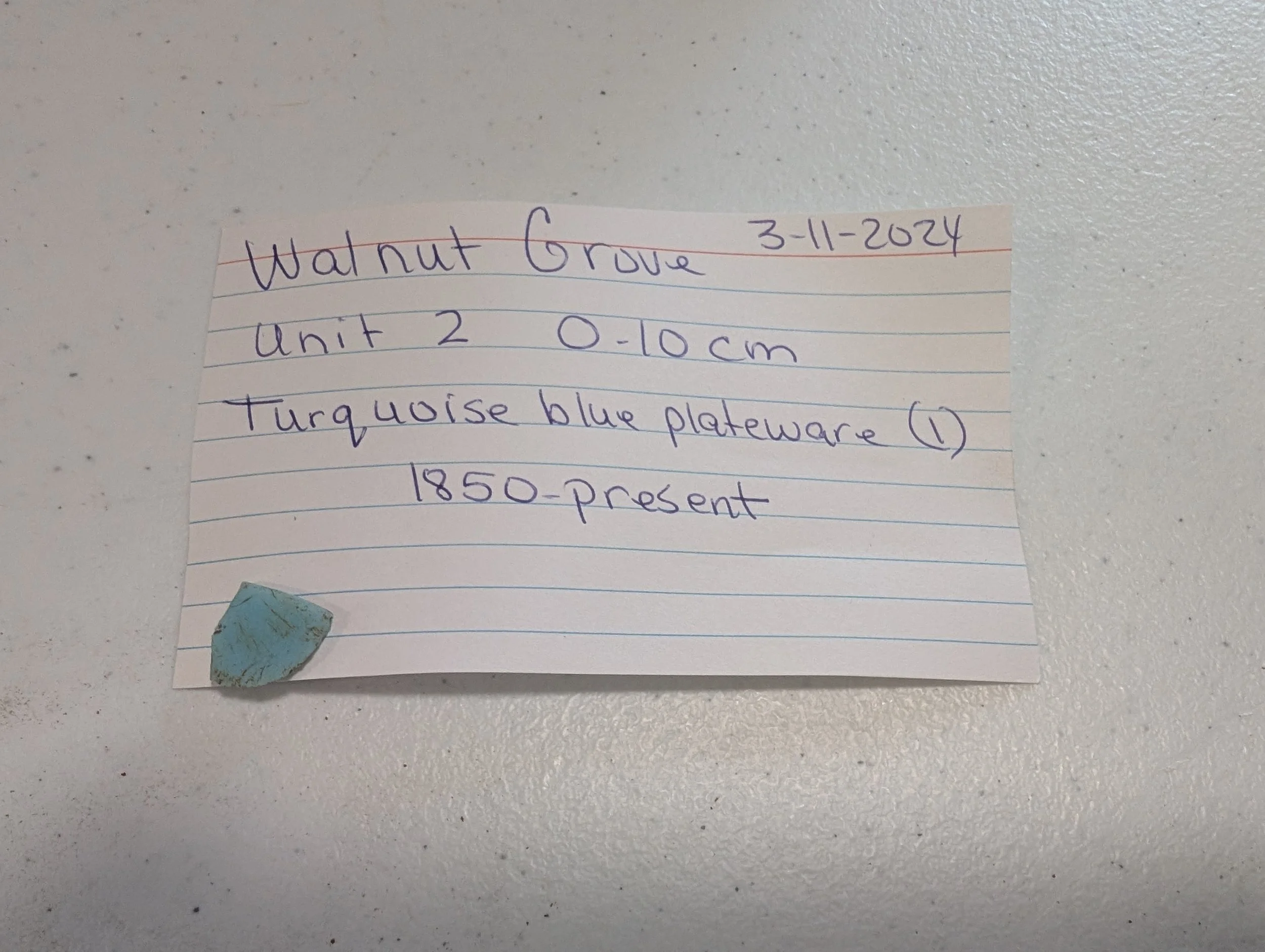

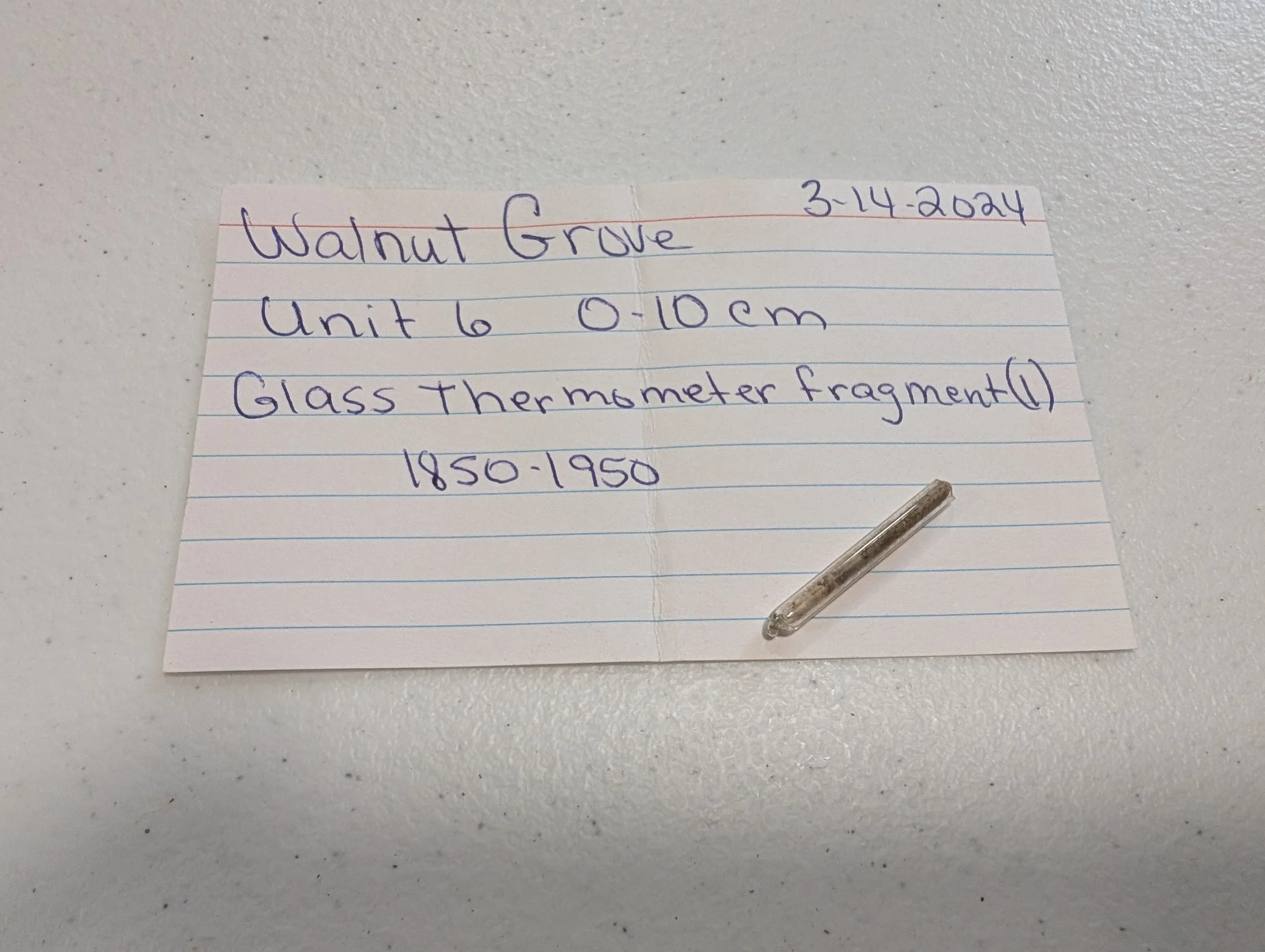

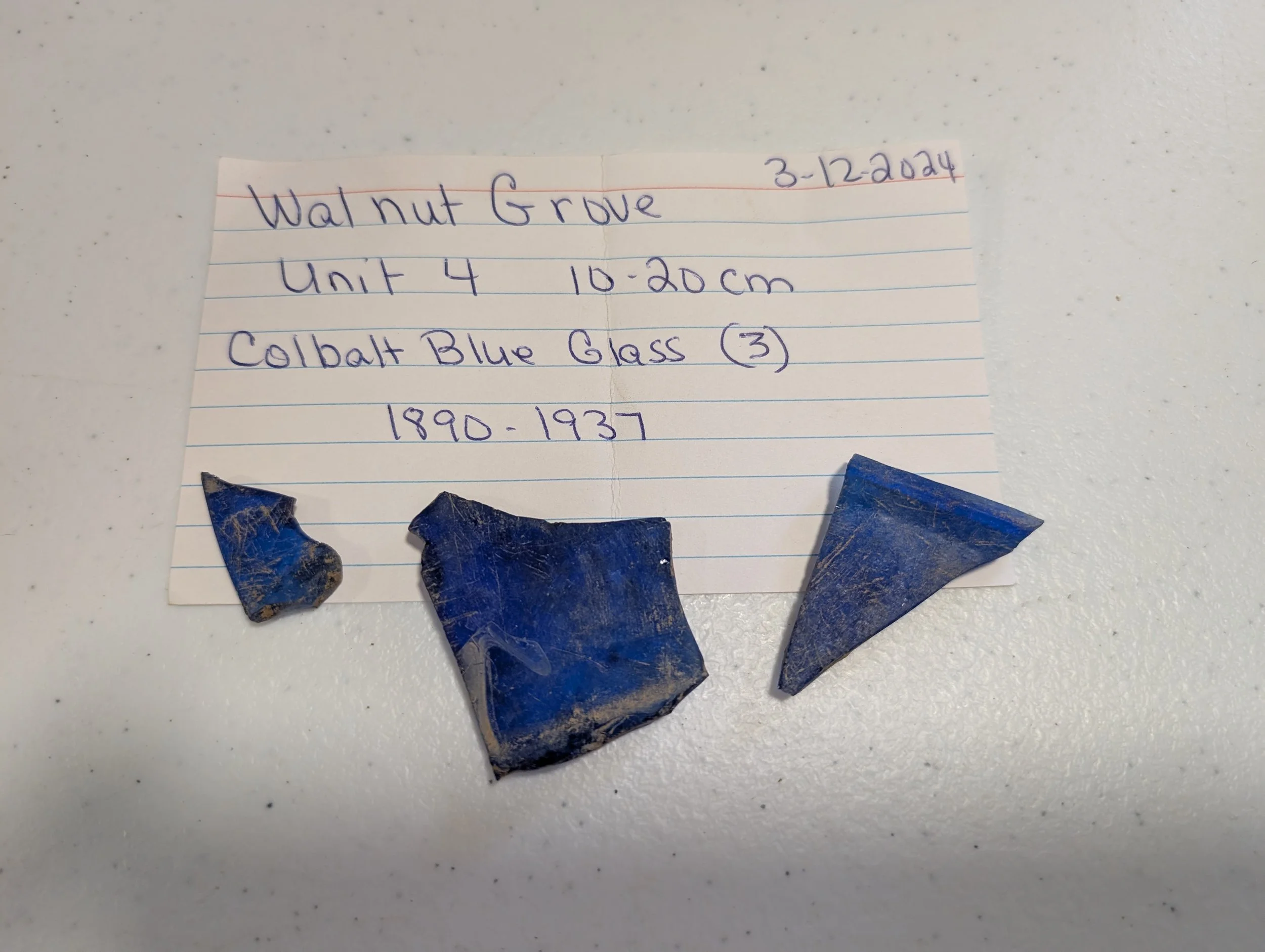

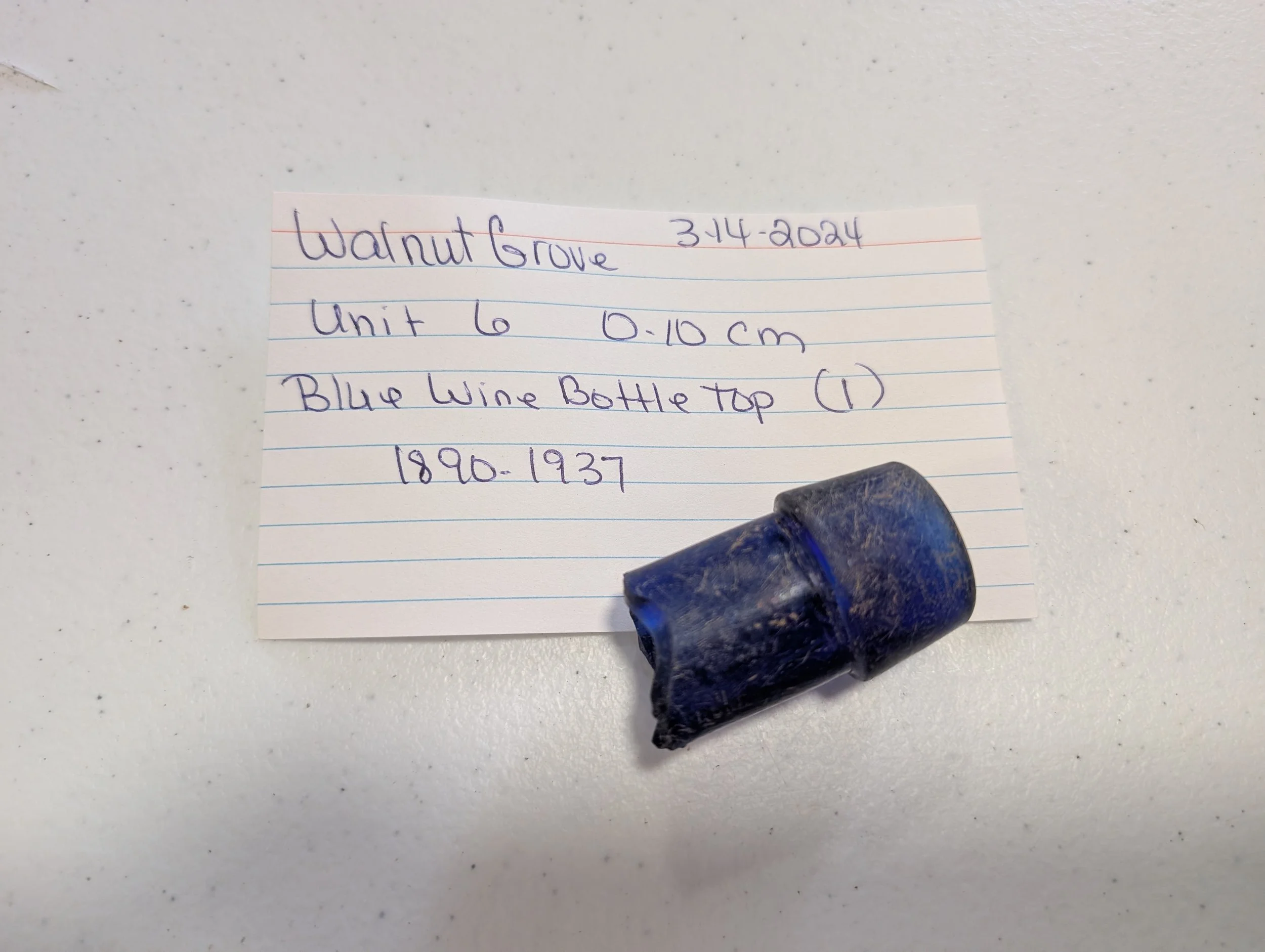

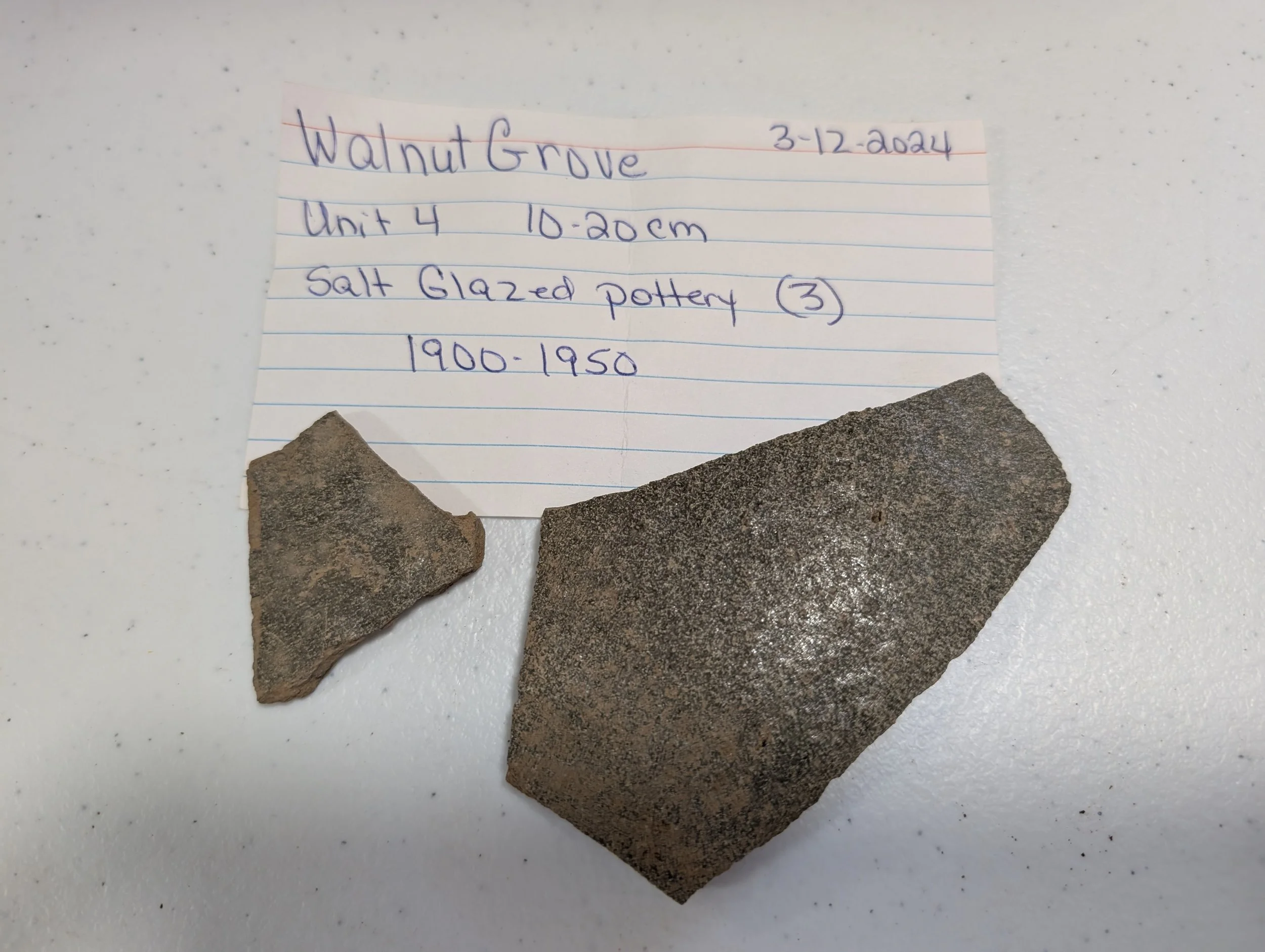

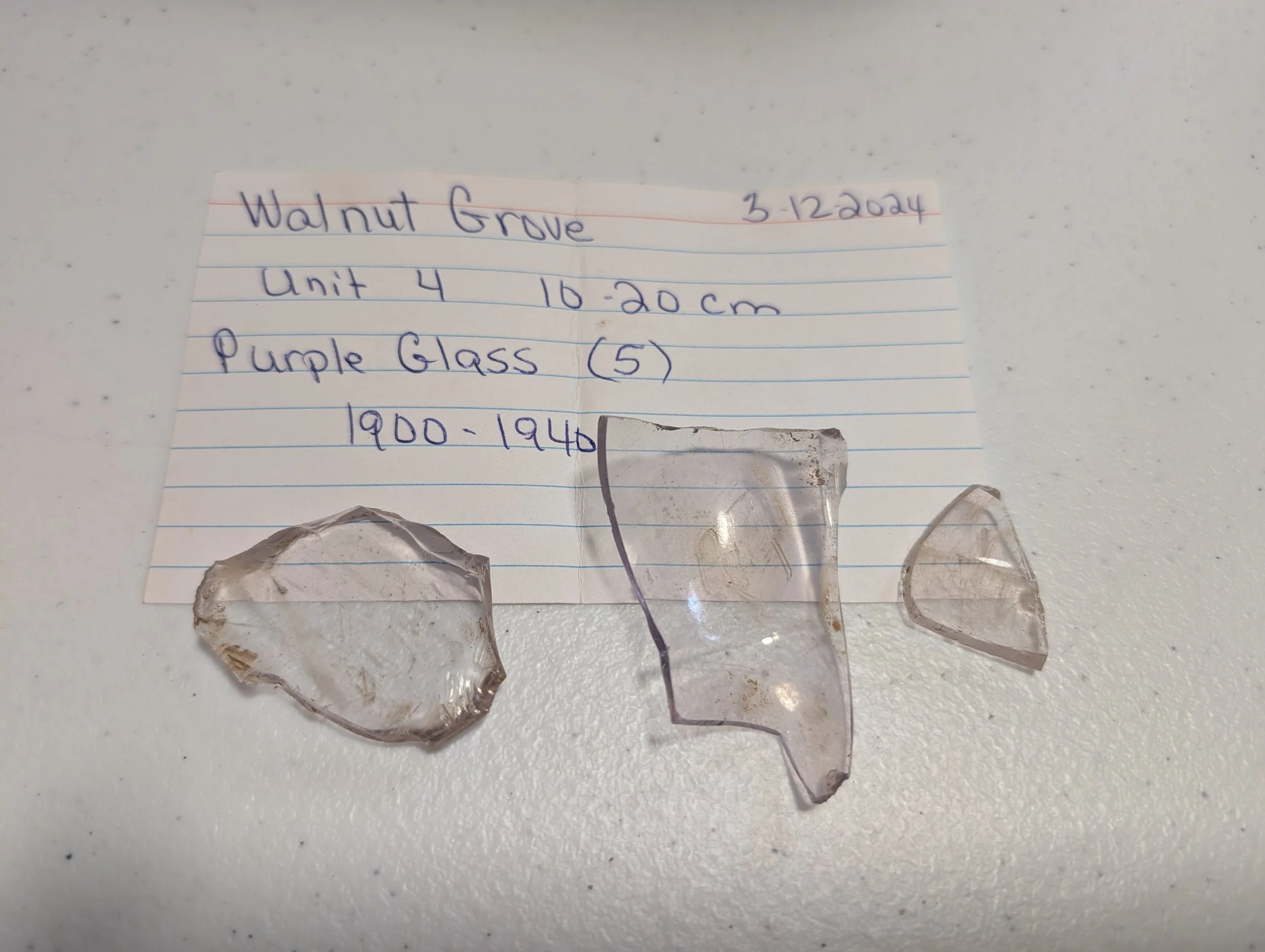

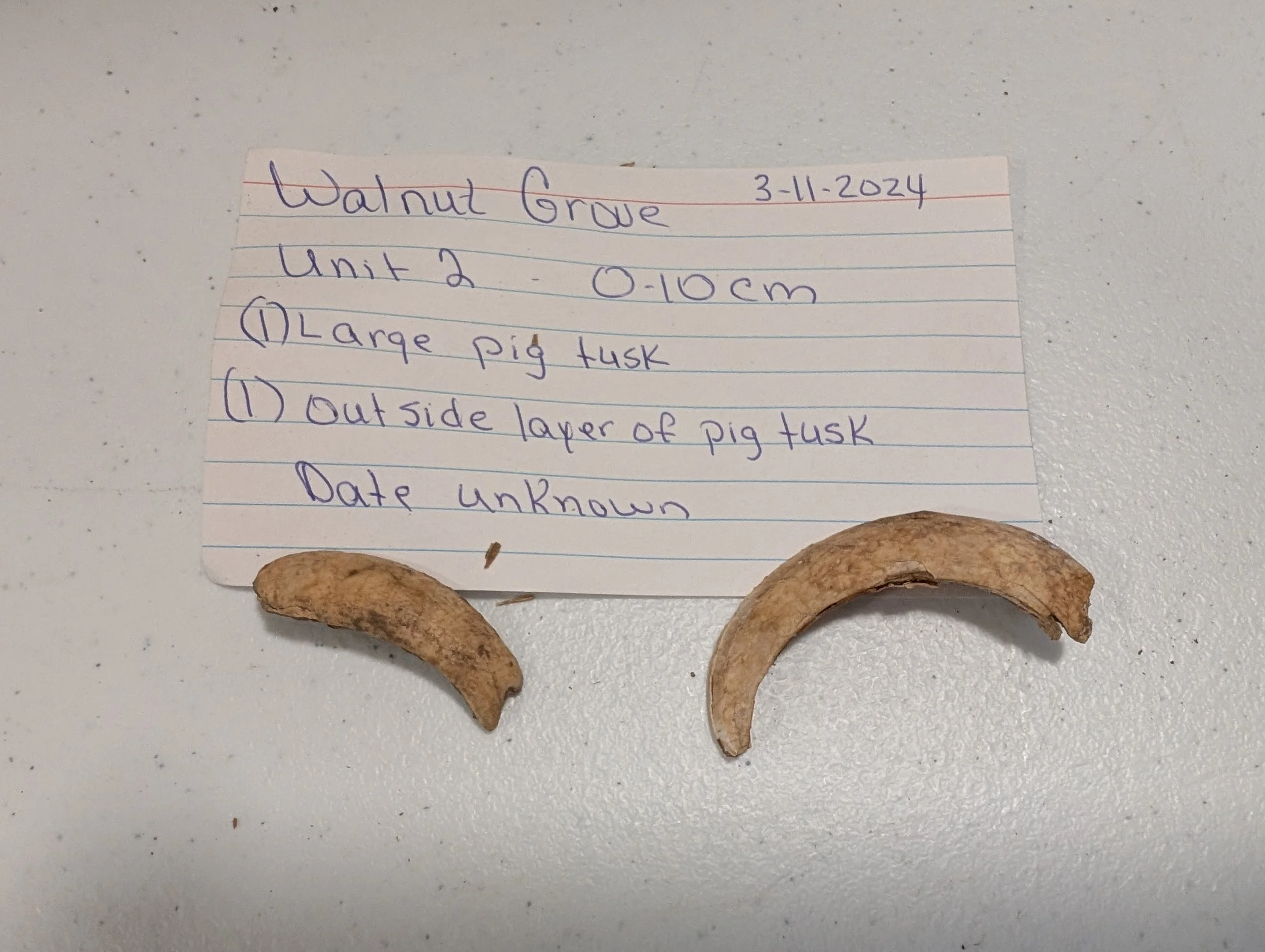

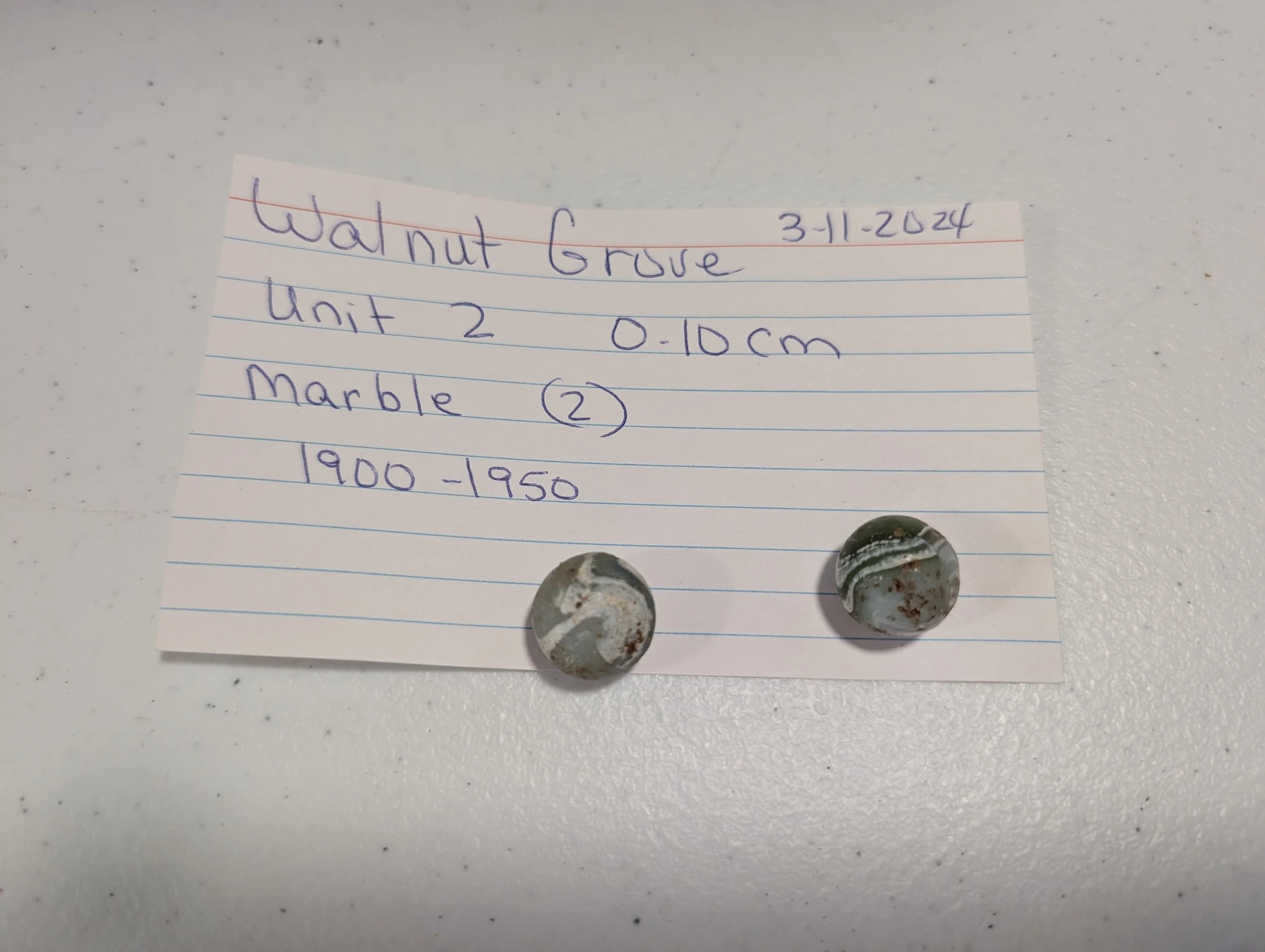

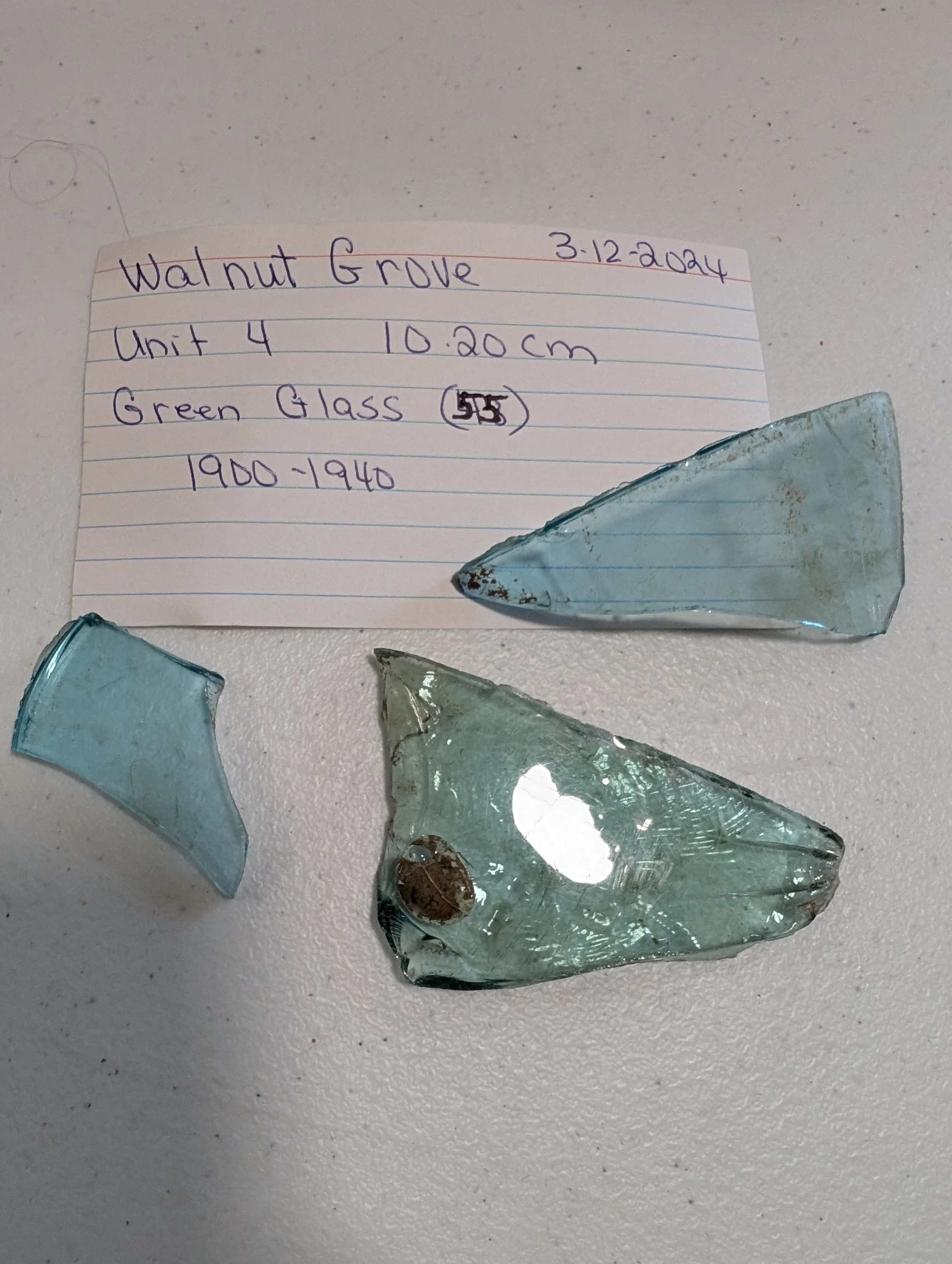

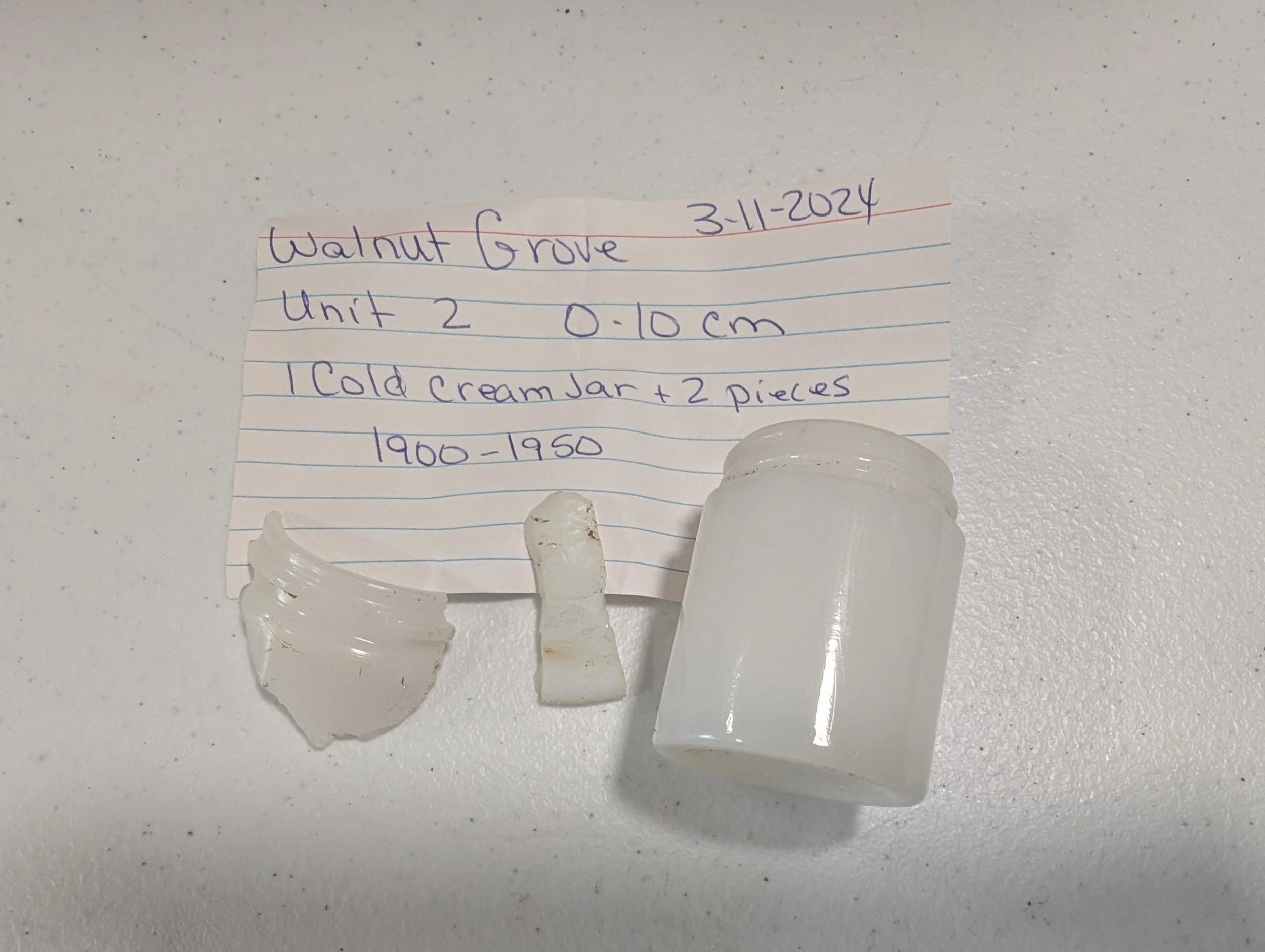

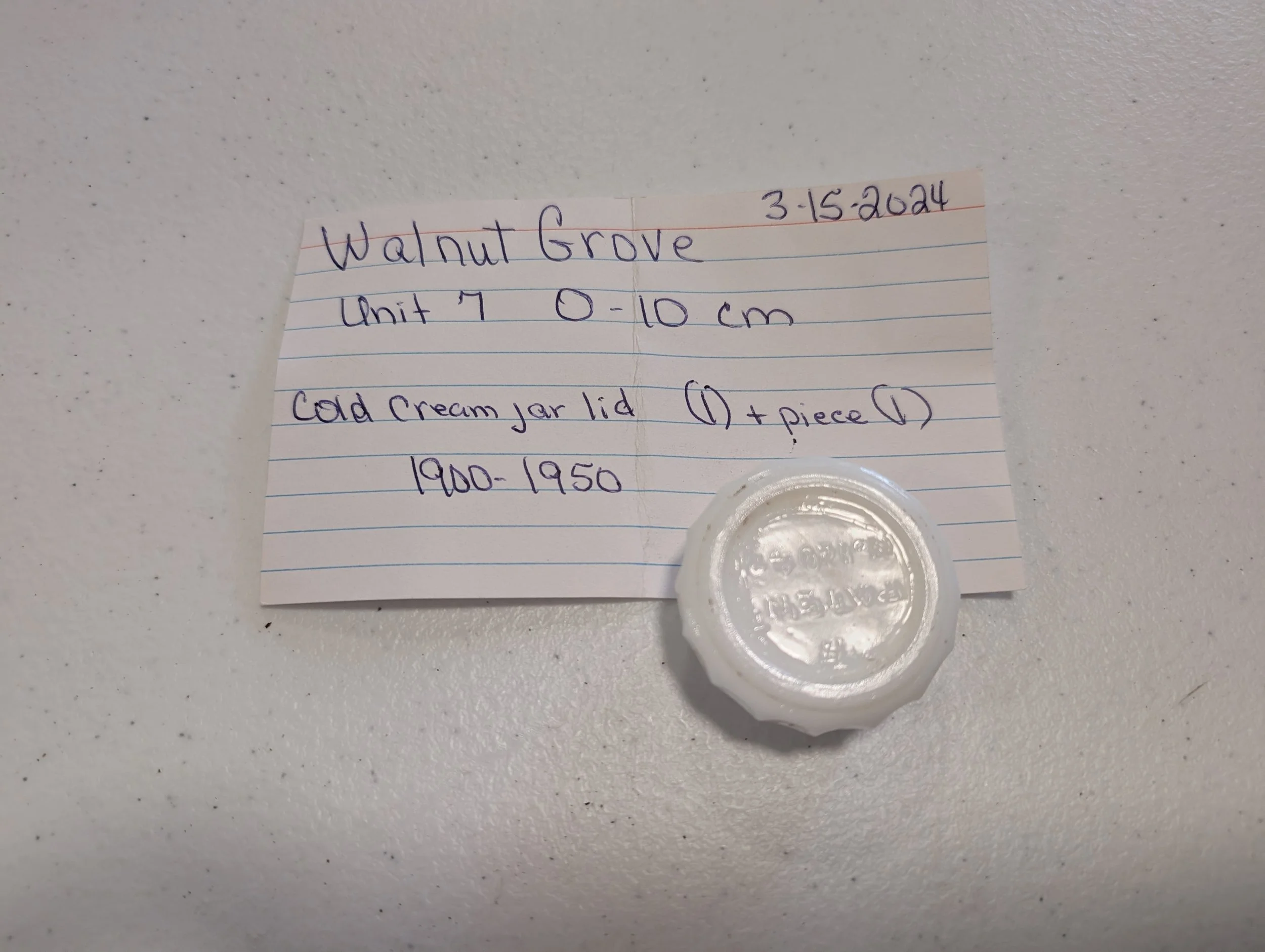

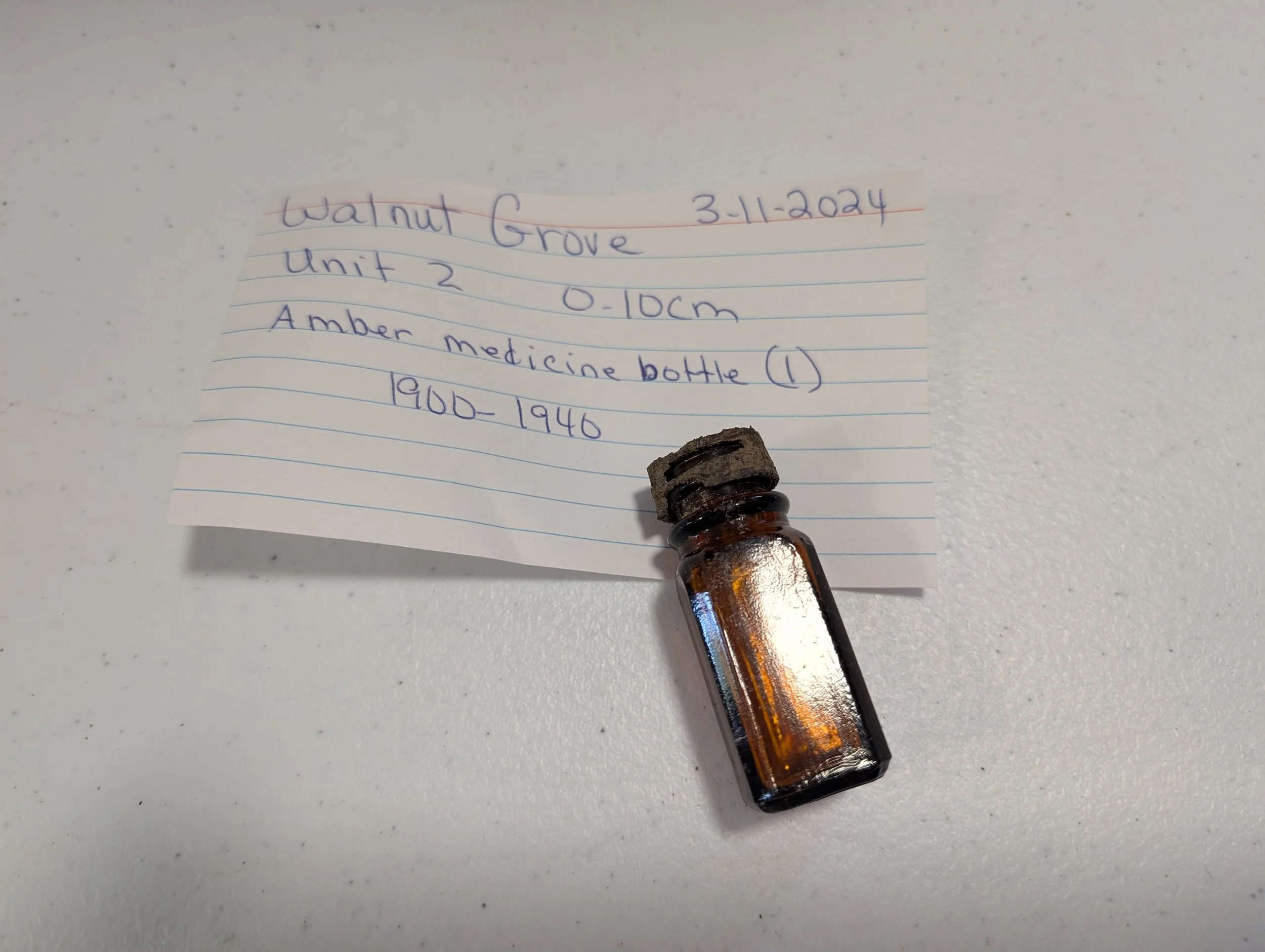

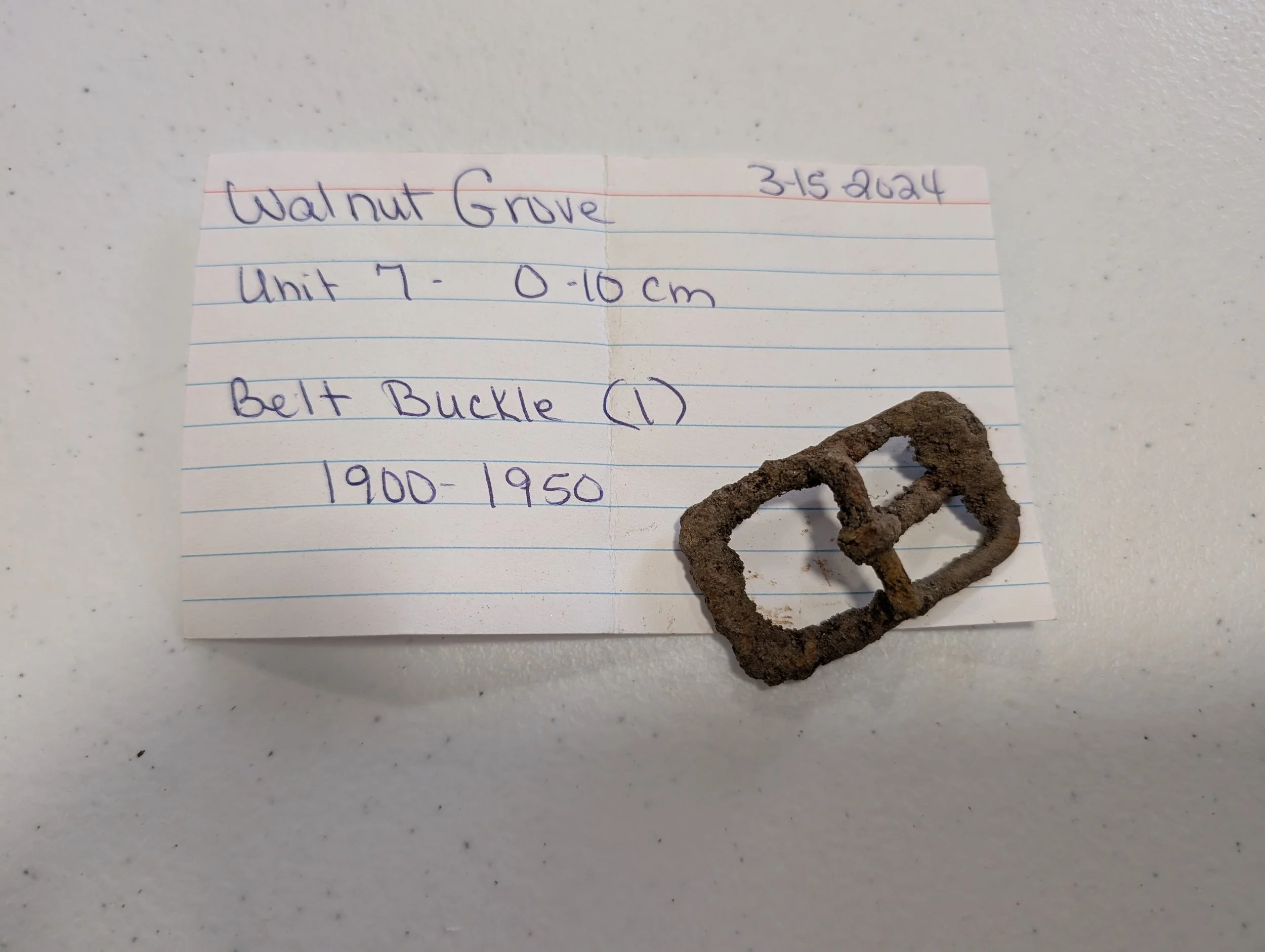

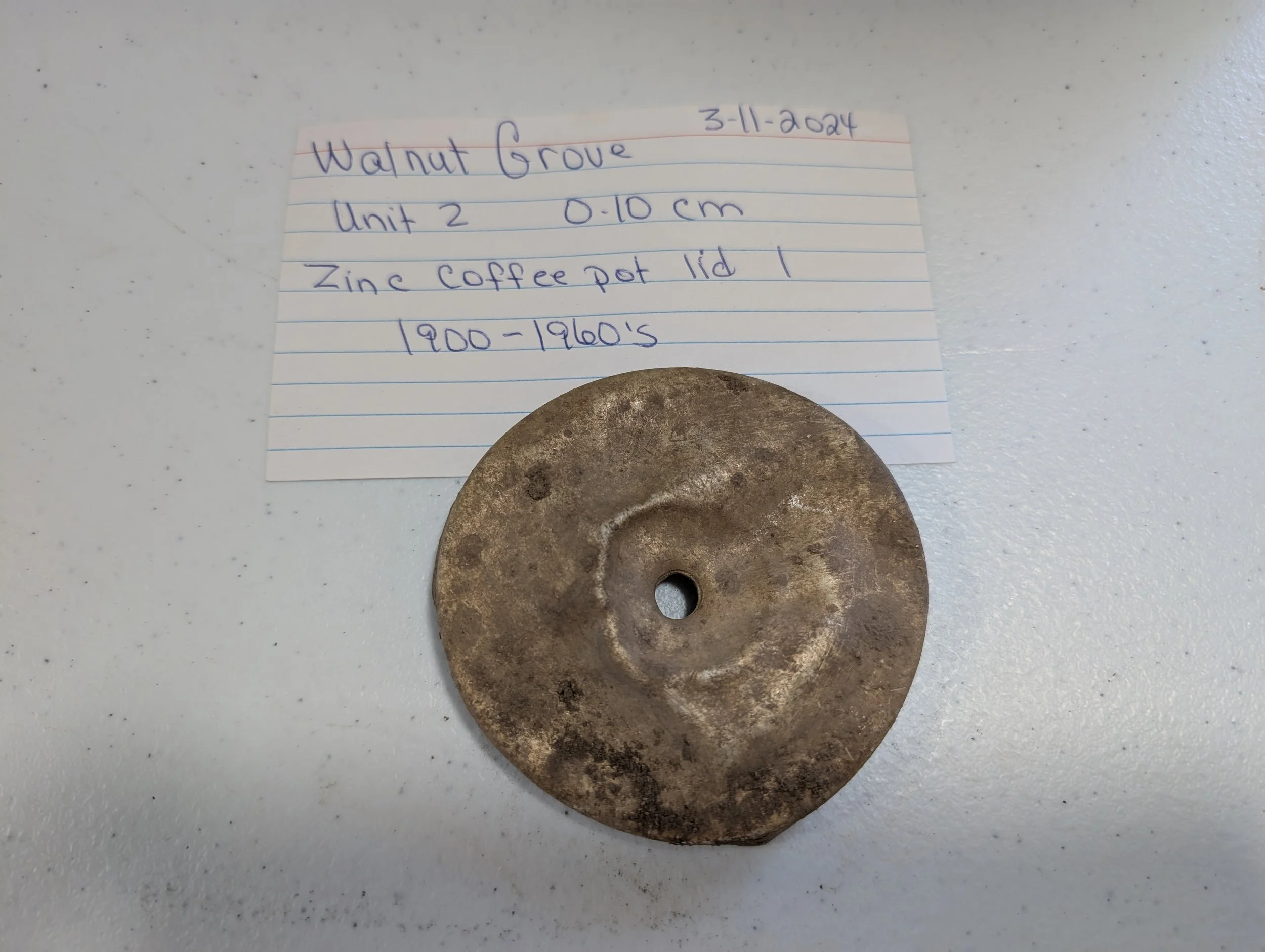

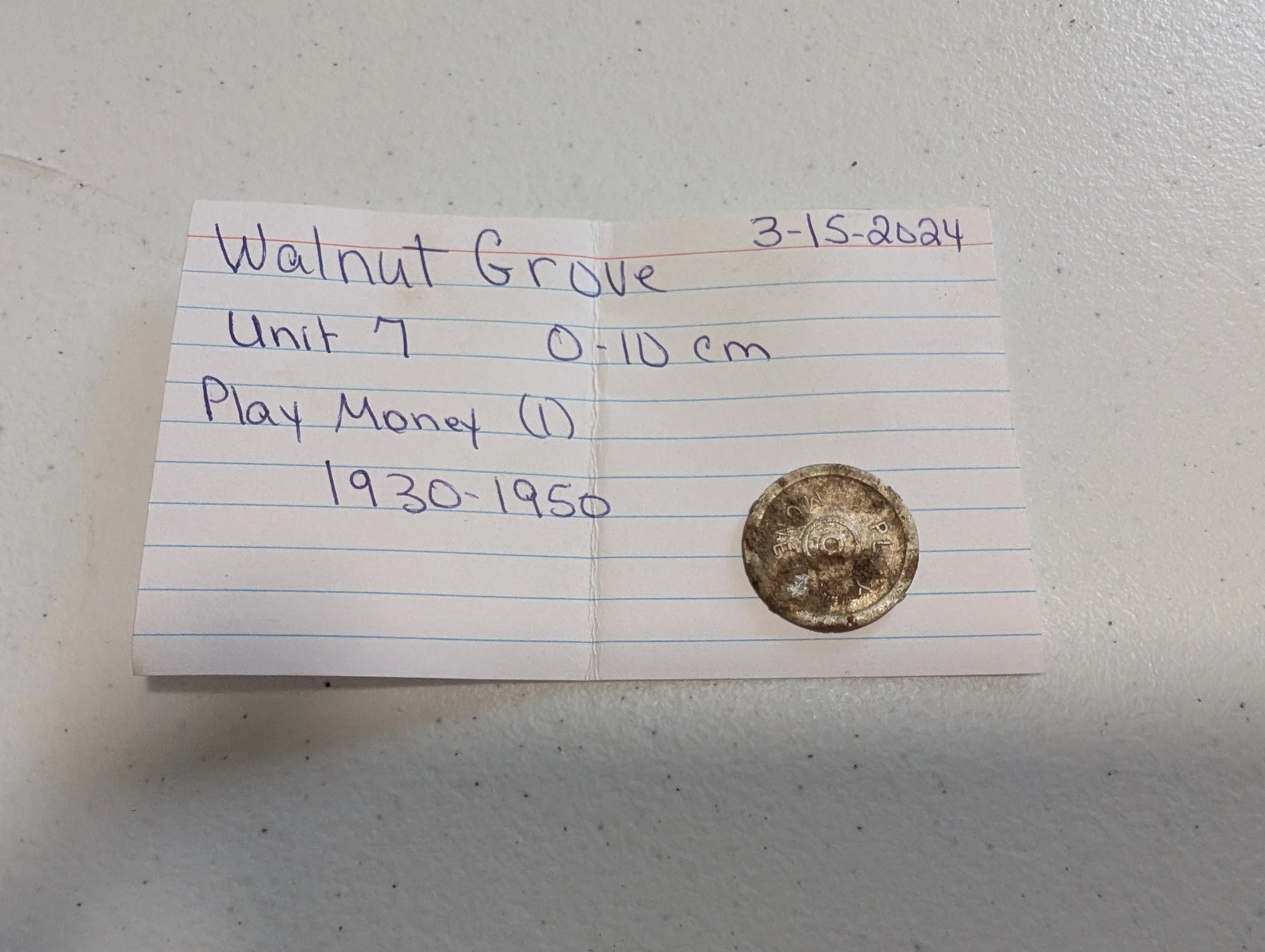

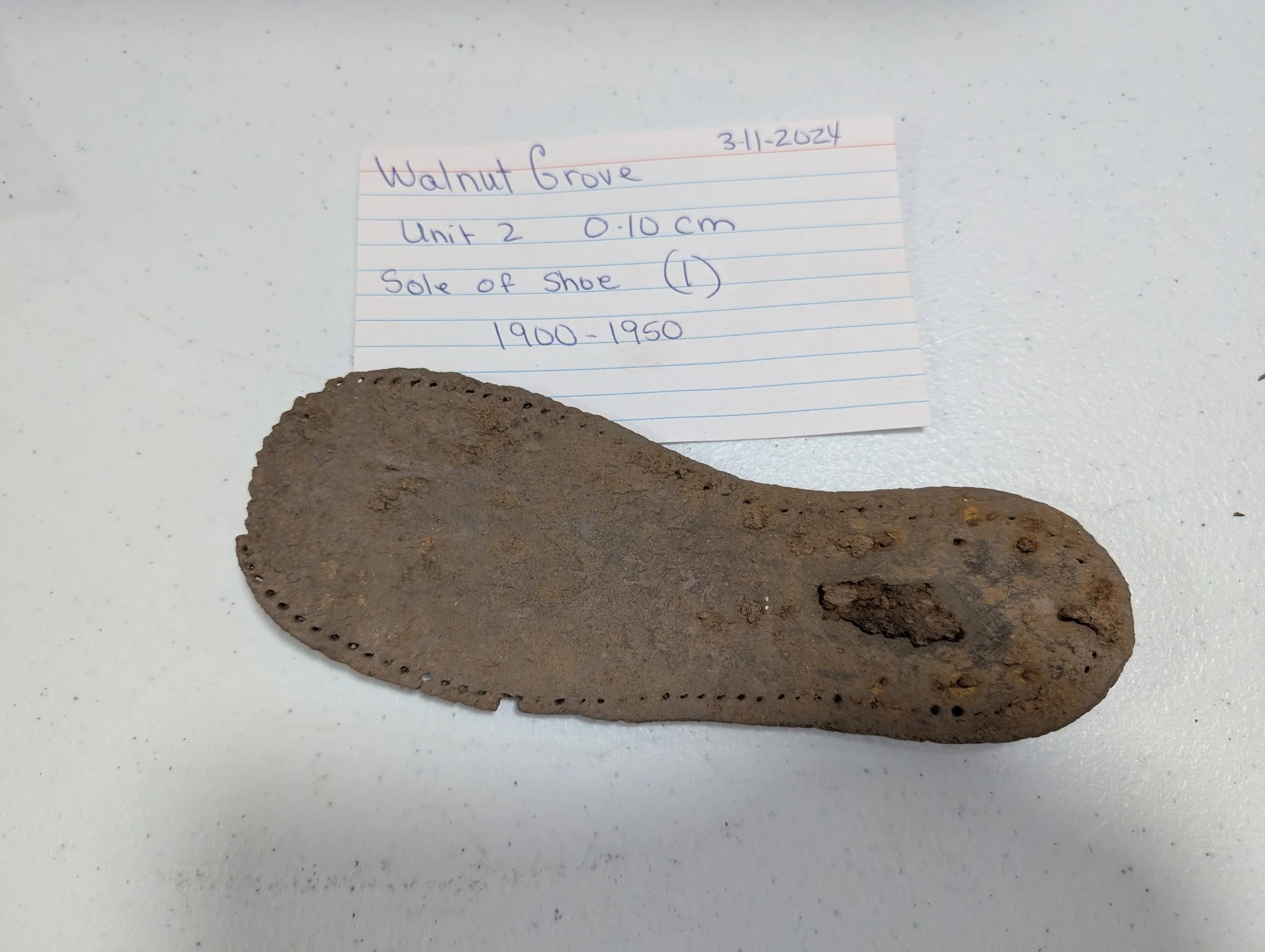

While the exact dates the cabin stood are unknown, archaeological evidence suggests it was inhabited from the late 1700s through the 1950s. After the Civil War, some emancipated individuals continued living at Walnut Grove as sharecroppers. The artifacts uncovered help tell the story of their lives, as well.

See photos of the dig and some artifacts below.

Slavery at Walnut Grove Plantation and Other Properties Owned by the Moore Family

While tours at Walnut Grove Plantation primarily focus on the colonial and Revolutionary War-era history of the Moore family, the site’s story spans nearly 200 years—much of it shaped by the institution of slavery. Over the years, the site has received criticism for not adequately addressing the lives of the enslaved individuals who lived and labored at Walnut Grove. Although many details are still unknown, records such as wills and census data provide us with valuable insight, including the names and numbers of those enslaved by the Moore family.

Early Records

Prior to the first U.S. census in 1790, documentation of enslaved people often appeared only in wills, estate inventories, and bills of sale. The 1790 census allows us to begin tracing the number of enslaved individuals owned by members of the Moore family. Charles Moore is recorded as owning 9 enslaved people; his son-in-law Andrew Barry (husband of Charles’s daughter Kate) owned 4; Thomas Moore owned 5; and Richard Barry (Andrew Barry’s brother and husband of Rosa Moore) owned 6.

In 1800, those numbers increased: Charles Moore owned 12 enslaved people, Thomas Moore had 11, Andrew Barry had 7, Richard Barry had 7, and Matthew Patton (who married both Rachel/Jane and Violet Moore at different times) owned 3.

Wills and Known Names

Charles Moore died in 1805, and his will listed 11 enslaved individuals by name: Robert, Dinna, Phillis, Nelly, Dove, Prince, Simon, Fanny, Bob, Tom, and Toney—six men and five women. This glimpse into the human lives behind the numbers underscores the importance of naming the enslaved whenever possible.

In 1810, the Moore family's holdings grew again. Dr. Andrew Barry Moore (who had just opened a medical practice after graduating from Dickinson College) owned 8 enslaved individuals; Andrew Barry owned 8; Charles Moore Jr. (now owner of Walnut Grove) had 10; Thomas Moore had 30; Richard Barry had 7; and Matthew Patton had 5.

By 1820, following the widespread adoption of the cotton gin, the Moore family's reliance on enslaved labor increased. That year, Andrew Barry Moore owned 30 enslaved people (15 males and 15 females), Charles Moore Jr. had 16 (10 males, 6 females), and Thomas Moore had 40 (25 males, 15 females).

Thomas Moore’s 1822 will lists 33 named individuals: Dublin, Lucy, Nelson, David, Hanna, Nancy, Frank, Flora, Charlotte, Emma, Little Prince, Deborah, John, Ned, Priscilla, Ephraim, Daniel, Dinah, Tom, Primus, Sam, Will, Grandison, Simon, Phillis, Little Ned, Little David, Simpson, Louisa, Sylvia, James, and Dublin (possibly listed twice). Based on names, we infer 20 were male, 12 were female, and one is of unknown gender.

The Plantation System

Today’s visitors may not associate the current Walnut Grove home with the stereotypical image of a plantation, yet by definition, it was one: a property worked by enslaved or indentured laborers to produce cash crops. While it is unclear whether the Moores brought enslaved individuals with them from North Carolina, it is likely. South Carolina became a Black-majority colony as early as 1708 and remained so until after the Civil War. At that time, wealth was often measured by land holdings and the number of enslaved people one owned. In its early years, Walnut Grove relied on enslaved labor for survival tasks such as cooking, farming, hunting, ironwork, and domestic service. Records also suggest that Charles Moore and his sons worked the land alongside those they enslaved.

Growth of Enslaved Holdings

In 1830, the census began including age ranges. Charles Moore Jr. had moved to Marion County, Alabama, and Andrew Barry Moore was operating the Walnut Grove post office. That year, Andrew Barry Moore owned 47 enslaved individuals: 23 males (ages ranged from under 10 to over 55) and 24 females (also spanning all age ranges). Mary Moore, widow of Thomas Moore, owned 3 enslaved girls under 24.

By 1840, Andrew Barry Moore remained the only one of Charles and Mary Moore’s children still living in Spartanburg County. That year, he owned 41 enslaved people: 21 males and 20 females.

Dr. Moore died in 1848. His will listed 51 enslaved people by name, including Thompson, Minus, Lea, Cealy, Jefferson, Harriet, Bailor (or Baily), Lucy, Sampson, Charlotte, Candy, Little Moses, Nueman, Stephen, Rachel, Rose, Ann, Margaret, Fanny, Nelly, Violet, Catherine, Betty, Frances, Simpson, Becky, Ransom, Grace, Charity, Duke, Nan, Big Moses, Bob, Sillah, Nancy, Allen, Arnus, Martha, Edy, Aleck, Mary, Sarah, Cynthia, Old Fanny, Chaney, Henery, Bill, John, Prince, and Isaac. Of these, 21 were likely male and 30 female.

The Final Years of Enslavement

After Dr. Moore’s death, Walnut Grove was willed to his eldest daughter, Margaret, though her mother retained the property until remarrying in 1854. By 1850, the U.S. conducted a separate census for enslaved individuals. That year, Dr. Moore’s widow, Nancy Montgomery Moore, owned 24 unnamed enslaved individuals—10 males and 14 females, ranging from infants to adults in their 60s.

In 1854, Margaret Moore married Samuel Means, who then lived at Walnut Grove. The 1860 slave census shows that Samuel Means owned 20 enslaved individuals (14 males, 6 females). That same year, Nancy Moore still owned 24 enslaved people, and Andrew Charles Moore, Dr. Moore’s eldest son, owned 26. Notably, Andrew Charles Moore was only 22 when he owned those 26 individuals. He died fighting for the Confederacy at the Second Battle of Bull Run in 1862 at the age of 24.

Dr. Moore’s youngest son, Thomas Jefferson Moore, owned a 49-year-old enslaved woman in 1860. By this time, many Moore descendants had either moved away or passed away.

Emancipation and Its Aftermath

After the Civil War ended in 1865, enslaved individuals were legally freed. However, many chose—or were forced by circumstance—to remain on the land where they had once been enslaved. Census records from the years following emancipation show multiple African American families with the surnames “Means” and “Moore,” likely adopted from former enslavers.

The first African American family with the surname Means listed in post-war records included a 47-year-old male farmer (name illegible), and his daughters Maletda (12), Alice (10), Barbary (8), Kelly (6), and Melinda (2). Other Means families included:

Noah and Eliza Means: Noah, 39, was a farmer; Eliza, 34, kept house. Their children Perryman, George, and Yalilha ranged from 7 to 12 years old.

Ralph and Ann Means: Ralph, 67, and Ann, 53, lived with children Amanda (19), Berlinda (13), and Lafayette (16).

Larah Means, age 21, and Mariah Means, age 23, were listed individually.

Jefferson Means, age 27, and his 25-year-old wife (name illegible) appear in the final listing.

Among African Americans with the surname Moore, one was Augustus Moore, a 23-year-old farmer. Another Moore family included John Moore, a 32-year-old farmer, and his wife Misty, age 27. Their children were Lydney (8), Jane (6), Franlt (4), and Edith (2).